This publication was published more than 5 years ago. The state of knowledge may have changed.

Risk and needs assessment regarding reoffending in adolescents

A systematic review and assessment of medical, economic, social and ethical aspects

Conclusions

There is a moderate certainty of evidence ⊕⊕⊕◯ that structured risk and needs assessment instruments provide guidance in assessing young people's risk of recidivism in violence and other crimes. The most studied instruments are Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY) and Youth Level of service/Case Management Inventory (YLS/CMI).

- We do not know which guidance clinical assessment without structured assessment instruments, i.e. assessment as usual, provides as there is very low certainty of evidence ⊕◯◯◯. The studies regarding assessment as usual are so different to one another that it is found not appropriate to add them in an analysis.

- There is a low certainty of evidence ⊕⊕◯◯ that structured risk and needs assessment instruments can identify those youths who are at low risk of recidivism in violence and other crimes. The certainty of evidence is based on limited number of studies that include low number of individuals

- There is a very low certainty of evidence ⊕◯◯◯ that structured risk and needs assessment instruments can identify those youths who are at a medium to high risk of relapse in violence and other crimes. The certainty of evidence is based on limited number of studies that include low number of individuals.

- There is a low certainty of evidence ⊕⊕◯◯ that professionals experience that structured risk and needs assessment instruments provide help by giving depth, support and transparency in the assessments, although they are considered as time consuming.

- More research is needed on how structured risk and needs assessment instruments affect risk management. Cost effectiveness and possible negative effects also need to be researched and followed up in practice.

Background and aim

Young people who have committed crimes can become relevant for investigations and assessments by the Swedish authorities, such as the social services, child and adolescent psychiatry, as well as by the State Institution Board's special youth homes. Structured risk and needs assessment instruments can be used as support for the investigations to assess adolescents’ risk of recidivism in violence and other crimes. Structured risk and needs assessments instruments also include assessing which needs should be cared for and managed with risk management.

In 2018, one fifth (about 19,700) of the prosecution decisions in Sweden were crimes committed by young people between 15 and 20 years old. Young people who have been prosecuted for crime have an increased risk of reoffending. Also, there is an increased risk of physical and mental health issues, falling outside the labor market and an increased risk of premature death. It is therefore important to provide these young people with an appropriate support to reduce the risk of further relapse.

The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate structured risk and needs assessment instruments that are used for young people, 12 to 18 years old, who already have committed a crime. Economic and ethical aspects, as well as a survey concerning practice to the Swedish social services, the child psychiatry services and State Institution Board's special youth homes, are included.

Methods

The systematic review is conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement and with SBU’s methodology (www.sbu.se/en/method). The protocol is registered in Prospero, CRD42018111968. Quantitative and qualitative studies with low or moderate risk of bias published during the period 2000-2019 were included. The Quadas2-instrument was used to assess the risk of bias in the quantitative studies whereas a CASP-version was used for studies with a qualitative design. A mail survey was sent randomly to the Swedish social services, to all child psychiatry services and State Institution Board's special youth homes in order to map the present clinical practice. Three educators representing services using SAVRY or YLS/CMI instruments were interviewed regarding resources and costs linked to material, training and time used for performing a structured risk and needs assessment.

Meta-analysis and narrative analysis were performed. The narrative analyses were based on the predictive validity using Area Under the Curve (AUC) values, whereas the meta-analyses were based on sensitivity and specificity data. ROC curves meeting a critical value of AUC ≥0.65, sensitivity ≥0.56 and specificity ≥0.71 were assessed as having a clinically important value.

The certainty of evidence was assessed according to GRADE or CERQual.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design

Longitudinal prospective design or retrospective studies with blinded follow up data (predictive validity), with a minimum of 6 months follow-up. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-experimental designs in order to compare the ability of the risk and needs assessment instruments to support risk management.

Studies were included if they (1) consisted of more than 10 participants; (2) provided data of at least 6 months follow-up; (3) were published from 2000 up to 31 January 2019; (4) were peer-reviewed publications in English, Swedish, Danish or Norwegian; (5) Swedish dissertations; and (6) conducted or reported on original empirical research.

Population

Adolescents aged 12-18 years who had committed any general crime or violence. Studies were excluded if more than 30% of the participants were children younger than 12 years of age or persons older than 18 years.

Index test

Risk- and needs assessment instruments for assessing the risk of reoffending. The instruments should include risk and protection factors in order to address the need of risk management for these young persons. Assessment as usual (i.e. without using structured assessment instruments), also serves as an index test. Exclusion criteria were:

- Instruments that are not defined as risk and needs assessment instruments (i.e. scales for measuring aggressive behavior, self-reports of criminal behavior, instruments for assessing psychopathy),

- Locally developed risk and need assessments instruments or data generated instruments as they can be difficult, or inappropriate, to generalize to other contexts, and

- Crimes of sexual nature, violence in close relationships, honor-related violence and violence-promoting extremism.

Reference test

Data from national or local registers such as police or court reports, self-reported data or forms for institutional violence registration.

Outcomes

- Recidivism in violence or general crimes (e.g. all crimes). Studies that have investigated all types of recidivism will be presented for general crime. If the study only investigates violent recidivism it will be presented as violent recidivism. The results of the outcome on predictive validity needs to be presented with AUC, values. These data could refer to boys or girls separately or to the whole group of adolescents.

- The instruments ability of matching treatment plans, specific interventions or leaves

- Effects on recidivism in criminality measured as registered criminality

- Experiences of risk and needs assessments among youth, parents and professionals

Language

English, Danish, Norwegian or Swedish.

Search period

From 2000 to 2019. Final search was conducted in January 2019.

Databases searched for literature

Main search: Academic Search Elite via EBSCO

- Medline via OvidSP

- PsycINFO via EBSCO

- Scopus via Elsevier

- SocINDEX via EBSCO

Simultaneous search of free text terms was also conducted in the EBSCO-bases CINAHL, ERIC, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection.

Additional search was conducted in the following databases: Campbell Library, DARE, HTA Database, NHS EED and Prospero from web sites, CRD (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination), FHI Folkhelseinstituttet, NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence), SCIE (Social Care Institute for Excellence). For economic aspects, an additional literature search was undertaken in January 2019 in Academic Search Elite through (EBSCO) and PsycINFO via (EBSCO) and Medline through OvidSP.

In April 2019, complementary searches were conducted regarding clinical assessment without structured assessment instruments, i.e. assessment as usual, through a contemporary search in the EBSCO databases and in Medline through OvidSP. Four citation searches of four selected studies were conducted in Scopus Elsevier, and reference lists were checked.

Client/patient involvement

No.

Results

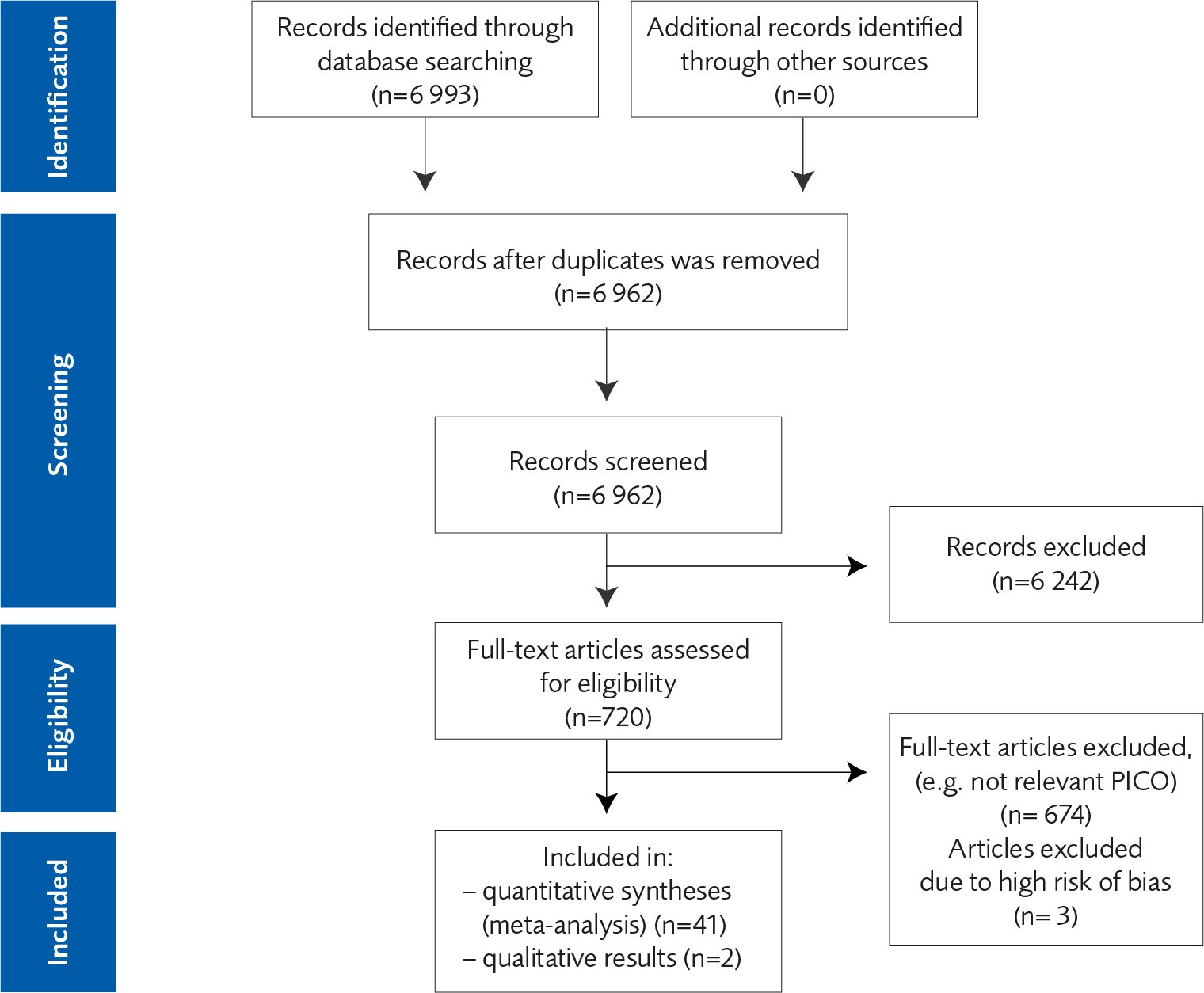

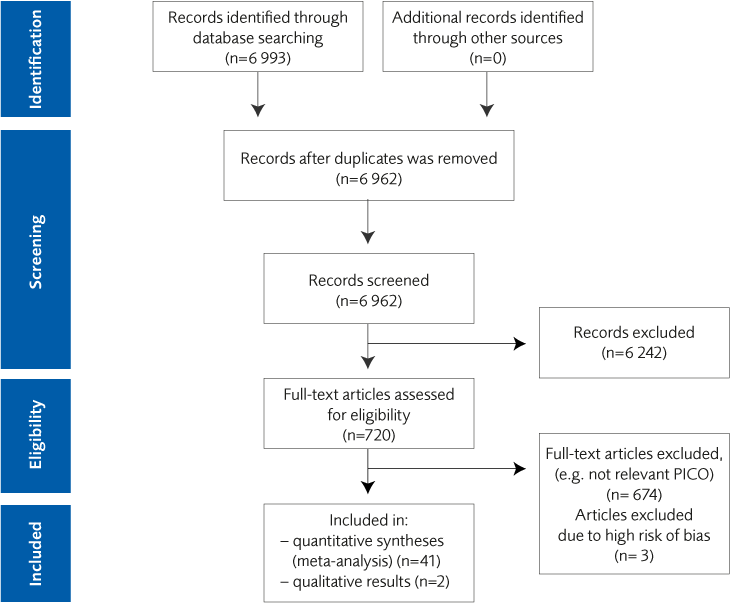

A total of 43 scientific articles were included, out of which 41 used AUC as statistical method (see flow chart link). The studies originated from 11 countries within Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. The number of young people per study varied from just over 50 to about 4,400 per study. A total of 21,698 young people was included in this report, out of which 82 percent were boys. Two articles were based on qualitative data reporting experiences among professionals.

The State Institution Board's special youth homes uses structured risk and needs assessment instruments, while its use is not as prominent in areas of child and adolescent psychiatry or in the social services.

Figure 1 Literature review flowchart.

| 1. Grade of evidence, GRADE, is assessed in a four-level scale; very low, low, moderate, and high cerainty. 2. The level of evidence differs between the measures (AUC, sensitivity and specificity) due to varying lengths of the confidence intervals, and thereby the down rating for precision are different. For AUC-values, no downrating has been made regarding precision due to significantly more studies and larger populations. |

|||

| Recidivism in violence and other crime | GRADE AUC ≥0,65 | GRADE Sensitivity ≥0,56 | GRADE Specificity ≥0,71 |

|---|---|---|---|

| All structured risk and need assessment instruments | |||

| Recidivism in violence | Moderate2 ⊕⊕⊕◯ |

Very low2 ⊕◯◯◯ |

Low2 ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Recidivism in other crime | Moderate ⊕⊕⊕◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Low ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| YLS/CMI (Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory) | |||

| Recidivism in violence | Moderate ⊕⊕⊕◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Low ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Recidivism in other crime | Moderate ⊕⊕⊕◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Low ⊕◯◯◯ |

| SAVRY (Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth) | |||

| Recidivism in violence | Moderate ⊕⊕⊕◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Low ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Recidivism in other crime | Low ⊕⊕◯◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

| Assessment as usual (i.e. without using structured assessment instrument) | |||

| Recidivism in violence | Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

| Recidivism in other crime | Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Health Economic Assessment

The systematic literature search did not identify any studies regarding economic aspects of the use of structured risk and needs assessment instruments.

Ethics

Assessing young people incorrectly can lead to an ethical dilemma. Many adolescents who are assessed to have an increased risk of relapse have a difficult life situation and may thus still need a support from the social services. However, while necessary it is important that this support does not become too interferent. The ethical tensions are similar regardless if the assessment is carried out with or without a structured risk and needs assessment instrument.

The full report in Swedish

The full report Risk- och behovsbedömning av ungdomar avseende återfall i våld och annan kriminalitet

Project group

Experts

- Johan Glad, National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm, Sweden

- Martin Lardén, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm; The Prison and Probation Service, Norrköping, Sweden

- Pia Nykänen, Gothenburg University, Sweden

- Susanne Strand, Örebro University, Sweden

- Helene Ybrandt, Umeå University, Sweden

SBU

- Therese Åström (Project Manager, Dr. Med. Sci)

- Gunilla Fahlström (Assistant Project Manager)

- Pia Johansson (Health Economist to 2018-07-24)

- Johanna Wiss (Health Economist from 2018-07-25 to 2018-10-05)

- Anna Ringborg (Health Economist from 2018-10-06)

- Anna Attergren Granath (Project Administrator)

- Agneta Brolund (Information Specialist)

External Reviewers

- Clara Hellner, Region Stockholm, Sweden

- Hugo Stranz, Stockholm university, Sweden

- Joakim Sturup, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden

Flow charts

Figure 1 Literature review flowchart.

References

- Rice ME, Harris GT. Comparing effect sizes in follow-up studies: ROC Area, Cohen's d, and r. Law Hum Behav 2005;29:615-20.

- SFS 2007:1233 Förordning med instruktion för Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering. Stockholm, Socialdepartementet; 2007.

- SFS 1962:700 Brottsbalk, Justitiedepartementet; 1962.

- Våldsrelaterade skador. Hämtad från: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/folkhalsorapportering-statistik/folkhalsans-utveckling/halsa/valdsrelaterade-skador/. In: Folkhälsomyndigheten, editor.; 2019.

- Morgan RE, Kena G. Criminal victimization, 2016. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Hämtad från: http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=6166. 2017.

- World Health Organization. Global status report on violence prevention. Genève: WHO. 2014.

- Brå. Kriminalstatisk 2018. Hämtat den 2019-09-30 från: https://www.bra.se/statistik/kriminalstatistik.html. In. Brottsförebyggande rådet, Stockholm; 2019.

- Farrington DP. Integrated Developmental and Life-course Theories of Offending. Somerset, US, Taylor & Francis Inc; 2008.

- Socialstyrelsen. Unga och brott i Sverige: underlagsrapport till Barns och ungas hälsa, vård och omsorg 2013. Stockholm: Hämtad från: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2013/2013-5-37.

- Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, et al. Female and male antisocial trajectories: from childhood origins to adult outcomes. Dev Psychopathol 2008;20:673-716.

- Bergman LR, Andershed AK. Predictors and outcomes of persistent or age-limited registered criminal behavior: a 30-year longitudinal study of a Swedish urban population. Aggress Behav 2009;35:164-78.

- Farrington DP, Ttofi MM, Coid JW. Development of adolescence-limited, late-onset, and persistent offenders from age 8 to age 48. Aggress Behav 2009;35:150-63.

- Lagerberg D, Sundelin C. Risk och prognos i socialt arbete med barn. Forskningsmetoder och resultat. Stockholm: Centrum för utvärdering av socialt arbete & Förlagshuset Gothia AB, 2000.

- Brå 2013:3 Skolundersökningen i årskurs nio. Resultat från skolundersökningar om brott 1995-2011. Hämtat från: http://bit.ly/2OtzyQm. 2013.

- Falk O, Wallinius M, Lundstrom S, Frisell T, Anckarsater H, Kerekes N. The 1% of the population accountable for 63% of all violent crime convictions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:559-71.

- Jolliffe D, Farrington DP, Piquero AR, Loeber R, Hill KG. Systematic review of early risk factors for life-course-persistent, adolescence-limited, and late-onset offenders in prospective longitudinal studies. Aggress Violent Behav 2017;33:15-23.

- Moffitt TE. Male antisocial behaviour in adolescence and beyond. Nat Hum Behav 2018;2:177-86.

- Rosell DR, Siever LJ. The neurobiology of aggression and violence. CNS Spectr 2015;20:254-79.

- Bonta J, Andrews DA. The psychology of criminal conduct. 6 ed. New York, Routledge; 2017.

- SFS 1990:52 Lag med särskilda bestämmelser om vård av unga, Stockholm, Socialdepartementet; 1990.

- Utreda barn och unga. Handbok för socialtjänstens arbete enligt socialtjänstlagen. Stockholm; 2015.

- Walker N. Crime and Insanity in England. One: The Historical Perspective. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press; 1968.

- Viljoen JL, Cochrane DM, Jonnson MR. Do risk assessment tools help manage and reduce risk of violence and reoffending? A systematic review. Law Hum Behav 2018;42:181-214.

- SBU. Riskbedömningar inom psykiatrin – kan våld i samhället förutsägas? En systematisk litteraturöversikt. Stockholm. Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering (SBU); 2005. SBU-rapport nr 175. ISBN 91-85413-03-8.

- Otto, R. Douglas, K.Handbook of violence risk assessment. New York, NY, US, Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2010.

- Douglas KS, Cox DN, Webster CD. Violence risk assessment: Science and practice. Legal and Criminological Psychology 1999;4:149-84.

- Ennis JB, Litwack RT. Psychiatry and the presumption of expertise: Flipping coins in the courtroom. California Law Review 1974:693-752.

- Douglas KS. Assessing risk for violence using structured professional judgment. American Psychology-Law Society Newsletter, 29(1), 12–15. 2009.

- Sturup J, Forsman M, Haggård U, Karlberg D, Johansson P. Riskbedömning i kriminalvård och rättspsykiatri: Sammanfattningsrapport. Norrköping: Kriminalvården. 2014.

- Andrews DA, Bonta J, Hoge RD. Classification for Effective Rehabilitation: Rediscovering Psychology. Crim Justice Behav 1990;17:19-52.

- Andrews DA, Bonta J. The psychology of criminal conduct, Sixth Edition (2017) New York, NY: Routledge, 2017.

- Andrews DA, Bonta J, Wormith JS. The recent past and near future of risk and/or need assessment. Crime & Delinquency 2016;52:7-27.

- SFS 2001:453 Socialtjänstlag Stockholm, Socialdepartementet; 2001.

- Tärnfalk M. Professionella yttranden : en introduktion till socialt arbete med unga lagöverträdare. Stockholm, Natur & kultur; 2014.

- SOSFS 2014:5. Socialstyrelsens föreskrifter och allmänna råd om dokumentation i verksamhet som bedrivs med stöd av SoL, LVU, LVM och LSS. Stockholm, Socialstyrelsen; 2014.

- Socialstyrelsen. Grundbok i BBIC. Barns behov i centrum. In, Stockholm; 2015.

- SFS 2017:30 Hälso- och sjukvårdslag. Stockholm, Socialdepartementet; 2017.

- SFS 1991:1128. Lag om psykiatrisk tvångsvård. Stockholm, Socialdepartementet; 1991.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5); 2013.

- Barn och ungdomspsykiatrin, Stockholms läns landsting. Riktlinjer till stöd för bedömning och behandling. Stockholm; 2015.

- Billstedt E, Hofvander B. Tidigt debuterande beteendestörning: förekomst och betydelse bland vålds- och sexualbrottsdömda. Norrköping: Kriminalvården. Hämtat från: http://bit.ly/2YZtfp3. 2009.

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593-602.

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:980-9.

- Richardson R, Trépel D, Perry A. Screening for psychological and mental health difficulties in young people who offend: a systematic review and decision model. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015 Jan. (Health Technology Assessment, No. 19.1.) Hämtad från: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK269083/ doi: 10.3310/hta19010. 2015.

- SFS 1998:603 Lag om verkställighet av sluten ungdomsvård. Stockholm, Justitiedepartementet L5; 1998.

- Statens institutionsstyrelse. Hämtar från: https://www.stat-inst.se/var-verksamhet/. den 2019-09-25.

- Jacobsson J. Rutin för behandlingsplanering. Behandlingsplacerade ungdomar. Statens institutionsstyrelse. Stockholm, Statens institutionsstyrelse; 2016.

- Frendin M. Personlig kommunikation 2018-04-27. SiS. In: Åström T, editor.; 2018.

- Sawyer AM, Borduin CM, Dopp AR. Long-term effects of prevention and treatment on youth antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2015;42:130-44.

- Swets JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988;240:1285-93.

- Salgado JF. Transforming the Area under the Normal Curve (AUC) into Cohen’s d, Pearson’s rpb, odds-ratio, and natural log odds-ratio: Two conversion tables. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context 2018;10:35-47.

- Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London, Chapman & Hall; 1997.

- Otto R, Douglas K. Handbook of violence risk assessment. New York, Routledge; 2010.

- Fryback DG, Thornbury JR. The efficacy of diagnostic imaging. Med Decis Making 1991;11:88-94.

- SBU. Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården. En handbok, 3 uppl. Stockholm 2014. http://www.sbu.se/metodbok.

- Rayyan QCRI. Hämtat den 2019-09-25 från: https://rayyan.qcri.org. In: Institute QCR, editor.

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Hämtad från: www.handbook.cochrane.org. In: Higgins J, Green S, editors.

- Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490.

- Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:383-94.

- Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gulmezoglu M, et al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001895.

- Anderson VR, Davidson WS, Barnes AR, Campbell CA, Petersen JL, Onifade E. The differential predictive validity of the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory: the role of gender. Psychology, Crime & Law 2016;22:666-77.

- Campbell C, Onifade E, Barnes A, Peterson J, Anderson V, Davidson W, et al. Screening offenders: The exploration of a Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory: (YLS/CMI) Brief Screener. J Offender Rehabil 2014;53:19-34.

- Catchpole REH, Gretton HM. The predictive validity of risk assessment with violent young offenders: A 1-year examination of criminal outcome. Crim Justice Behav 2003;30:688-708.

- Childs K, Frick PJ, Ryals JS, Lingonblad A, Villio MJ. A Comparison of empirically based and structured professional judgment estimation of risk using the structured assessment of violence risk in youth. Youth Violence & Juvenile Justice 2014;12:40-57.

- Chu CM, Lee Y, Zeng G, Yim G, Tan CY, Ang Y, et al. Assessing youth offenders in a non-Western context: The predictive validity of the YLS/CMI ratings. Psychol Assess 2015;27:1013-21.

- Chu CM, Yu H, Lee Y, Zeng G. The utility of the YLS/CMI-SV for assessing youth offenders in Singapore. Crim Justice Behav 2014;41:1437-57.

- Cuervo K, Villanueva L. Analysis of risk and protective factors for recidivism in Spanish youth offenders. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2015;59:1149-65.

- Cuervo K, Villanueva L. Prediction of recidivism with the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (Reduced Version) in a sample of young Spanish offenders. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2018;62:3562-80.

- Dolan MC, Rennie CE. The structured assessment of violence risk in youth as a predictor of recidivism in a United Kingdom cohort of adolescent offenders with conduct disorder. Psychol Assess 2008;20:35-46.

- Gammelgård M, Koivisto A-M, Eronen M, Kaltiala-Heino R. The predictive validity of the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY) among institutionalised adolescents. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 2008;19:352-70.

- Gammelgard M, Koivisto AM, Eronen M, Kaltiala-Heino R. Predictive validity of the structured assessment of violence risk in youth: A 4-year follow-up. Crim Behav Ment Health 2015;25:192-206.

- Hilterman EL, Nicholls TL, van Nieuwenhuizen C. Predictive validity of risk assessments in juvenile offenders: Comparing the SAVRY, PCL:YV, and YLS/CMI with unstructured clinical assessments. Assessment 2014;21:324-39.

- Jones NJ, Brown SL, Robinson D, Frey D. Validity of the youth assessment and screening instrument: A juvenile justice tool incorporating risks, needs, and strengths. Law Hum Behav 2016;40:182-94.

- Lodewijks HPB, de Ruiter C, Doreleijers TAH. Gender differences in violent outcome and risk assessment in adolescent offenders after residential treatment. Int J Forensic Ment Health 2008 A;7:133-46.

- Lodewijks HPB, Doreleijers TAH, de Ruiter C. SAVRY risk assessment in violent Dutch adolescents: Relation to sentencing and recidivism. Crim Justice Behav 2008 B;35:696-709.

- Lodewijks HPB, Doreleijers TAH, de Ruiter C, Borum R. Predictive validity of the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY) during residential treatment. Int J Law Psychiatry 2008;31:263-71.

- Luong D, Wormith JS. Applying risk/need assessment to probation practice and its impact on the recidivism of young offenders. Crim Justice Behav 2011;38:1177-1199.

- McGrath AJ, Thompson AP, Goodman-Delahunty J. Differentiating predictive validity and practical utility for the Australian adaptation of the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory. Crim Justice Behav 2018;45:820-39.

- Meyers JR, Schmidt F. Predictive validity of the Structured Assessment for Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY) with juvenile offenders. Crim Justice Behav 2008;35:344-55.

- Mori T, Takahashi M, Kroner DG. Can unstructured clinical risk judgment have incremental validity in the prediction of recidivism in a non-Western juvenile context? Psychol Serv 2017;14:77-86.

- Olver ME, Stockdale KC, Wong SCP. Short and long-term prediction of recidivism using the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory in a sample of serious young offenders. Law & Human Behavior (American Psychological Association) 2012;36:331-44.

- Ortega-Campos E, Garcia-Garcia J, Zaldivar-Basurto F. The predictive validity of the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth for Young Spanish Offenders. Front Psychol 2017;8:577.

- Penney SR, Lee Z, Moretti MM. Gender differences in risk factors for violence: an examination of the predictive validity of the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth. Aggress Behav 2010;36:390-404.

- Perrault RT, Vincent GM, Guy LS. Are risk assessments racially biased?: Field study of the SAVRY and YLS/CMI in probation. Psychol Assess 2017;29:664-78.

- Rennie C, Dolan M. Predictive validity of the youth level of service/case management inventory in custody sample in England. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 2010;21:407-25.

- Schmidt F, Hoge RD, Gomes L. Reliability and validity analyses of the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory. Crim Justice Behav 2005;32:329-44.

- Schmidt F, Sinclair SM, Thomasdóttir S. Predictive validity of the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory with youth who have committed sexual and non-sexual offenses: The utility of professional override. Crim Justice Behav 2016;43:413-30.

- Shepherd SM, Luebbers S, Ogloff JRP, Fullam R, Dolan M. The predictive validity of risk assessment approaches for young Australian offenders. Psychiatry, Psychology & Law 2014;21:801-17.

- Stockdale KC, Olver ME, Wong SCP. The validity and reliability of the Violence Risk Scale–Youth Version in a diverse sample of violent young offenders. Crim Justice Behav 2014;41:114-38.

- Takahashi M, Kroner DG, Mon T. A Cross-validation of the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (YLS/CMI) Among Japanese Juvenile Offenders. Law & Human Behavior (American Psychological Association) 2013;37:389-400.

- Thompson AP, McGrath A. Subgroup differences and implications for contemporary risk-need assessment with juvenile offenders. Law Hum Behav 2012;36:345-55.

- Thompson AP, Pope Z. Assessing juvenile offenders: Preliminary data for the Australian Adaptation of the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (Hoge & Andrews, 1995)*. Aust Psychol, November 2005 2005;40(3):207 –4.

- Upperton RA, Thompson AP. Predicting juvenile offenders recidivism: Risk--need assessment and juvenile justice officers. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 2007;14:138-46.

- van der Put CE, Stams GJ, Dekovic M, van der Laan PH. Predictive validity of the Washington State Juvenile Court Pre-Screen Assessment in the Netherlands: the development of a new scoring system. Assessment 2014;21:92-107.

- Vaswani N, Merone L. Are there risks with risk assessment? A study of the predictive accuracy of the Youth Level of Service–Case Management Inventory with young offenders in Scotland. Br J Soc Work 2014;44:2163-81.

- Viljoen JL, Gray AL, Shaffer C, Bhanwer A, Tafreshi D, Douglas KS. Does reassessment of risk improve predictions? A framework and examination of the SAVRY and YLS/CMI. Psychol Assess 2017;29:1096-1110.

- Viljoen JL, Shaffer CS, Muir NM, Cochrane DM, Brodersen EM. Improving case plans and interventions for adolescents on probation: The implementation of the SAVRY and a structured case planning form. Crim Justice Behav 2019;46:42-62.

- Villanueva L, Gomis-Pomares A, Adrian JE. Predictive validity of the YLS/CMI in a sample of Spanish young offenders of Arab descent. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2019;63:1914-30.

- Zhang J. Testing the predictive validity of the LSI-R using a sample of young male offenders on probation in Guangzhou, China. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2016;60:456-68.

- Zhou J, Witt K, Cao X, Chen C, Wang X. Predicting Reoffending Using the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY): A 5-year follow-up study of male juvenile offenders in Hunan province, China. PLoS ONE 2017;12:1-11.

- Åström T, Gumpert CH, Andershed A-K, Forster M. The SAVRY improves prediction of reoffending. Res Soc Work Pract 2017;27:683-94.

- McGrath A, Thompson AP. The relative predictive validity of the static and dynamic domain scores in risk-need assessment of juvenile offenders. Crim Justice Behav 2012;39:250-63.

- Vincent GM, Paiva-Salisbury ML, Cook NE, Guy LS, Perrault RT. Impact of risk/needs assessment on juvenile probation officers' decision making: Importance of implementation. Psychol Public Policy Law 2012;18:549-76.

- Åström T. Intervention planning in assessment of adolescent offenders: Does SAVRY improve matching of crimogenic needs ti interventions.

- Guy LS, Nelson RJ, Fusco-Morin SL, Vincent GM. What do juvenile probation officers think of using the SAVRY and YLS/CMI for case management, and do they use the instruments properly? Int J Forensic Ment Health 2014;13:227-41.

- Ring J. Rapport 2017:8. Hämtad från: https://www.bra.se/download/18.4c494ddd15e9438f8ad38d51/1510929097847/2017_8_Kostnader_for_brott.pdf. In. Brottsförebyggande rådet, Stockholm; 2017.

- Personlig kommunikation Mikaela Baum, Socialstyrelsen Uppsala 2018-09-21. In: Åhström T, editor. SAVRY nätverket, Uppsala; 2018.

- Personlig kommunikation Marie Frendin, Statens institutionsstyrelse 2018-08-31. In: Åhström T, editor., Stockholm; 2018.

- Personlig kommunikation med Maria Helander BUP öppenvård. 2018-09-26. In: Åhström T, editor.; 2018.

- Austin J. How much risk can we take? The misuse of risk assessment in corrections. Federal Probation, 70(2), s. 58-63. 2006.

- Briggs DB. Conceptualising risk and need: The rise of actuarialism and the death of welfare? Practitioner assessment and intervention in the youth offending service. Youth Justice 2013;13:17-30.

- Maurutto P, Hannah-Moffat K. Understanding risk in the context of the youth criminal justice act. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 2007;49:465-91.

- Nielssen O. Scientific and ethical problems with risk assessment in clinical practice. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2013;47:1198-9.

- Szmukler G, Rose N. Risk assessment in mental health care: values and costs. Behav Sci Law 2013;31:125-40.

- Van Damme L, Fortune C-A, Vandevelde S, Vanderplasschen W. The good lives model among detained female adolescents. Aggress Violent Behav 2017:179–89.

- Viljoen JL, Shaffer CS, Gray AL, Douglas KS. Are adolescent risk assessment tools sensitive to change? A framework and examination of the SAVRY and the YLS/CMI. Law Hum Behav 2017;41:244-57.

- Fakultativt protokoll till konventionen den 20 november 1989 (SÖ 1990:20) om barnets rättigheter vid indragning av barn i väpnade konflikter. New York Utrikesdepartementet; 2000.

- Rocque M, Welsh BC, Greenwood PW, King E. Implementing and sustaining evidence-based practice in juvenile justice: a case study of a rural state. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2014;58:1033-57.

- SFS 2017:30 Hälso- och sjukvårdslag. Stockholm, Socialdepartementet.

- Akademikerförbundet SSR. Etik i socialt arbete: Etisk kod för socialarbetare. Stockholm: Hämtad från: https://akademssr.se/sites/default/files/files/etik_och_socialt_arbete.pdf 2015.

- Sveriges Läkarförbund. Läkarförbundets etiska regler. Hämtad från: https://slf.se/rad-och-stod/etik/lakarforbundets-etiska-regler/ 2017.

- Sveriges Psykologförbund. Yrkesetiska principer för psykologer i Norden. Hämtad från: https://www.psykologforbundet.se/globalassets/yrket/yrkesetiska--principer-for-psykologer-i-norden.pdf In; 1998.

- World Psychiatric Organisation (1996). Madrid declaration on ethical standards for psychiatric practice. Hämtad från: http://www.wpanet.org/current-madrid-declaration. In; 1996.

- Sundell K, Vinnerljung B, Ryburn M. Social workers’ attitudes towards family group conferences in Sweden and the UK. Child & Family Social Work 2001;6:327-36.

- Gustle L-H, Knut S, Hansson K, Andrée Löfholm C. MST project in Sweden - What factors affect the tendency of social workers to refer subjects to the research project? Int J Soc Welf. 2008.

- Strijbosch ELL, Huijs JAM, Stams GJJM, Wissink IB, van der Helm GHP, de Swart JW, & , et al. The outcome of institutional youth care compared to non-institutional youth care for children of primary school age and early adolescence: A multi-level meta-analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev, 58, 208-218. 2015.

- Vincent GM, Guy LS, Perrault RT, Gershenson B. Risk assessment matters, but only when implemented well: A multisite study in juvenile probation. Law Hum Behav 2016;40:683-696.

- Evidensbaserad praktik i socialtjänsten 2007, 2010, 2013 och 2016. Kommunala enhetschefer om EBP under ett decennium. Hämtad från: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2017-9-9.pdf. In. Socialstyrelsen, Stockholm; 2017.

- Andershed H, Fredriksson J, Engelholm K, Ahlberg R, Berggren S, Andershed A-K. Initial test of a new risk-need assessment instrument for youths with or at risk for conduct problems: ESTER-assessment. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2010;5:488–92.

- Harris GT, Rice ME, Quinsey VL. Violent offenders: Appraising and managing risk (3d ed.) Washington, DC: American psychological Association. 2015.

- Lipsey MW. The primary factors that characterize effective interventions with juvenile offenders: A meta-analytic overview. Victims & Offenders 2009;4:124-47.

- Singh JP. Predictive validity performance indicators in violence risk assessment: a methodological primer. Behav Sci Law 2013;31:8-22.

- SBU. Insater i öppenvård för att förebygga ungdomars återfall i brott. En systematisk översikt och utvärdering av ekonomiska, sociala och etiska aspekter: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); SBU-rapport nr 308. ISBN 978-91-88437-50-1.

- Halligan S, Altman DG, Mallett S. Disadvantages of using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve to assess imaging tests: a discussion and proposal for an alternative approach. Eur Radiol 2015;25:932-9.

- SBU. Instrument för bedömning av suicidrisk. En systematisk litteraturöversikt. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); SBU-rapport nr 242. ISBN 978-91-85413-86-7.

- Fazel S, Singh JP, Doll H, Grann M. Use of risk assessment instruments to predict violence and antisocial behaviour in 73 samples involving 24 827 people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;345:e4692.

- Schwalbe CS. Risk assessment for juvenile justice: A meta-analysis. Law Hum Behav 2007;31:449-62.

- Schwalbe CS. A Meta-Analysis of Juvenile Justice Risk Assessment Instruments: Predictive Validity by Gender. Crim Justice Behav 2008;35:1367-81.

- Vose B, Cullen F, Smith P. The empirical status of the Level of Service Inventory. Federal Probation 2008;72:22-9.

- Edens J, Campbell J, Weir J. Youth Psychopathy and Criminal Recidivism: A Meta-Analysis of the Psychopathy Checklist Measures. Law Hum Behav 2007;31:53-75.

- Olver M, Stockdale K, Wormith J. Thirty years of research on the level of service scales: A meta-analytic examination of predictive accuracy and sources of variability. Psychol Assess 2013;26.

- Pusch N, Holtfreter K. Gender and risk assessment in juvenile offenders: A meta-analysis. Crim Justice Behav 2017;45:56-81.

- Olver ME, Stockdale KC, Wormith JS. Risk assessment with young offenders: A meta-analysis of three assessment measures. Crim Justice Behav 2009;36:329-53.

- Singh JP, Grann M, Fazel S. A comparative study of violence risk assessment tools: A systematic review and metaregression analysis of 68 studies involving 25,980 participants. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:499-513.

- Singh JP, Fazel S, Gueorguieva R, Buchanan A. Rates of violence in patients classified as high risk by structured risk assessment instruments. Br J Psychiatry 2014;204:180-7.

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Share via Email