Fear of childbirth, depression and anxiety during pregnancy

A systematic review and assessment of medical, economic, social and ethical aspects. An HTA Report

Summary and conclusions

Conclusions

- Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) can be used to identify pregnant women with a fear of childbirth that needs to be further assessed (low certainty).

- The effect of interventions to treat fear of childbirth could not be estimated because there are too few studies.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can reduce the symptoms of depression in pregnant women with depression (low certainty). We estimate the effect to be clinically relevant and of moderate size. The effect of CBT on anxiety during pregnancy could not be estimated because there are too few studies.

- Psychoeducation can reduce depressive symptoms in pregnant women with depression, anxiety disorders or both (low certainty). We estimate the effect as too small to be clinically relevant.

- The effect could not be estimated for Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), Behavioral Activation, Mindfulness, Counselling, and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (PDT), because studies are too few and heterogenous.

Background

In Sweden, pregnant women contact maternal health care early in pregnancy to get their own and their expected child’s health monitored by midwives. The care includes psychosocial assessments, as well as regular health controls, risk assessments, fetal diagnostics, breastfeeding promotion, and antenatal classes. Psychosocial assessments guide the midwife in the development of a care plan for the pregnant woman and her partner, and in determining whether the couple needs referral for additional support.

Fear of childbirth may be described as a broad term for various emotional difficulties related to pregnancy and childbirth. It is reported by first time mothers as well as mothers who have previously given birth. Fear of childbirth in this report refers to a clinically relevant level of fear of childbirth, i.e. a level that interferes with how she lives her daily life and involves significant suffering. The prevalence of fear of childbirth varies depending on country, context and method of assessment used. In Sweden it is estimated to be 14%.

The symptoms of depression and anxiety experienced during pregnancy do not differ from those experienced at other times. In Sweden, pregnant women with mild depression or anxiety disorder are usually offered counselling with a midwife, counselor, or psychologist. When moderate depression or anxiety disorder is suspected or confirmed, they are offered short-term psychotherapy, pharmacological treatment, or both. In cases of severe depression, pharmacological treatment is usually needed, stand-alone, or as a supplement to psychotherapy, and the midwife will recommend that the woman contact a psychiatrist. In this report, we focus on psychosocial interventions to treat mild to moderate depression and anxiety disorders during pregnancy.

Aim

In the systematic review of this report, we assess:

- the diagnostic accuracy of assessment methods to identify fear of childbirth

- the effect of interventions for fear of childbirth

- the effect of psychosocial interventions for mild to moderate depression, and anxiety disorders during pregnancy.

The report also includes a health economic assessment and a chapter on ethical considerations.

Method

A systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement. The protocol was registered in Prospero (CRD42020162166). The certainty of evidence was assessed using GRADE.

The ethical chapter is based on two separate discussion meetings held by an ethicist with patient associations and experts in the project group.

The project group assessed clinical relevance of calculated effects sizes. Assessments were based om clinical expertise and reliability of the scales used. If different scales were used, effect sizes were calculated as standardized mean difference (SMD). For ease of interpretation, SMD was then transformed back into one of the original scales.

Inclusion criteria

Specific inclusion criteria for the review questions are specified in tables 1, 2, and 3. Common inclusion criteria for all review questions are specified in table 4.

| Question | What is the diagnostic accuracy of rating scales to identify clinically relevant fear of childbirth? |

| Population | Women with suspected fear of childbirth |

| Index test | All types of tests of fear of childbirth |

| Reference test | Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire (W-DEQ) |

| Outcome | Sensitivity, specificity |

| Study design | Cross-sectional studies |

| Question | What is the effect of interventions for clinically relevant fear of childbirth? |

| Population | Women with clinically relevant fear of childbirth (i.e. population must have been selected based on elevated levels of fear of childbirth) |

| Intervention/Exposure | All interventions for fear of childbirth |

| Comparison | No intervention, placebo, care as usual or other intervention |

| Outcome | Fear of childbirth, mode of delivery, other scales on mental state, quantified experience of treatment, quality of life (measured with validated instruments), complications during childbirth, pain relief, medications during childbirth. |

| Study design | Primary: randomised controlled studies. Secondary: prospective and controlled but not randomised studies. |

| Treatment and follow-up times | No restrictions |

| Question | What is the effect of psychosocial interventions for mild to moderate depression, and anxiety disorders during pregnancy? |

| Population | Pregnant women with mild to moderate levels of depression, anxiety, or both (diagnosed or symptoms measured with validated instruments) |

| Intervention/Exposure | Counselling, psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, psychodynamic therapy (including modifications of these) |

| Comparison | Primary: no intervention, care as usual, or placebo, secondary: other treatment |

| Outcome | Primary: degree of symptoms, diagnosis, quality of life (measured with validated instruments), secondary: satisfaction with treatment, side effects, sick leave, parent's attachment to the child (antenatal), suicidal ideation, suicide attempt or completed suicide |

| Study design | Primary: randomised controlled studies, secondary: prospective controlled but not randomised studies |

| Treatment and follow-up times | No restrictions on treatment duration, follow-up during pregnancy |

| Language | Search period | Databases searched | Additional databases searched for health economic studies |

| English, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish | Final searches were performed August to November 2020. For review questions 2 and 3 we concluded that the NICE guidelines would include all relevant studies. Thus, the NICE guidelines were scanned for studies until 2013 and our search results were only scanned from 2013 onwards. | CINAHL® with Full Text via EBSCOhost, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via Wiley, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Central) via Wiley, Embase via Elsevier, Medline via Ovid, APA PsycInfo via EBSCOhost | International HTA Databas via INAHTA, Database of Reviews of Effect (DARE) via Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), NHS EED via Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), HTA Database via Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) |

Results

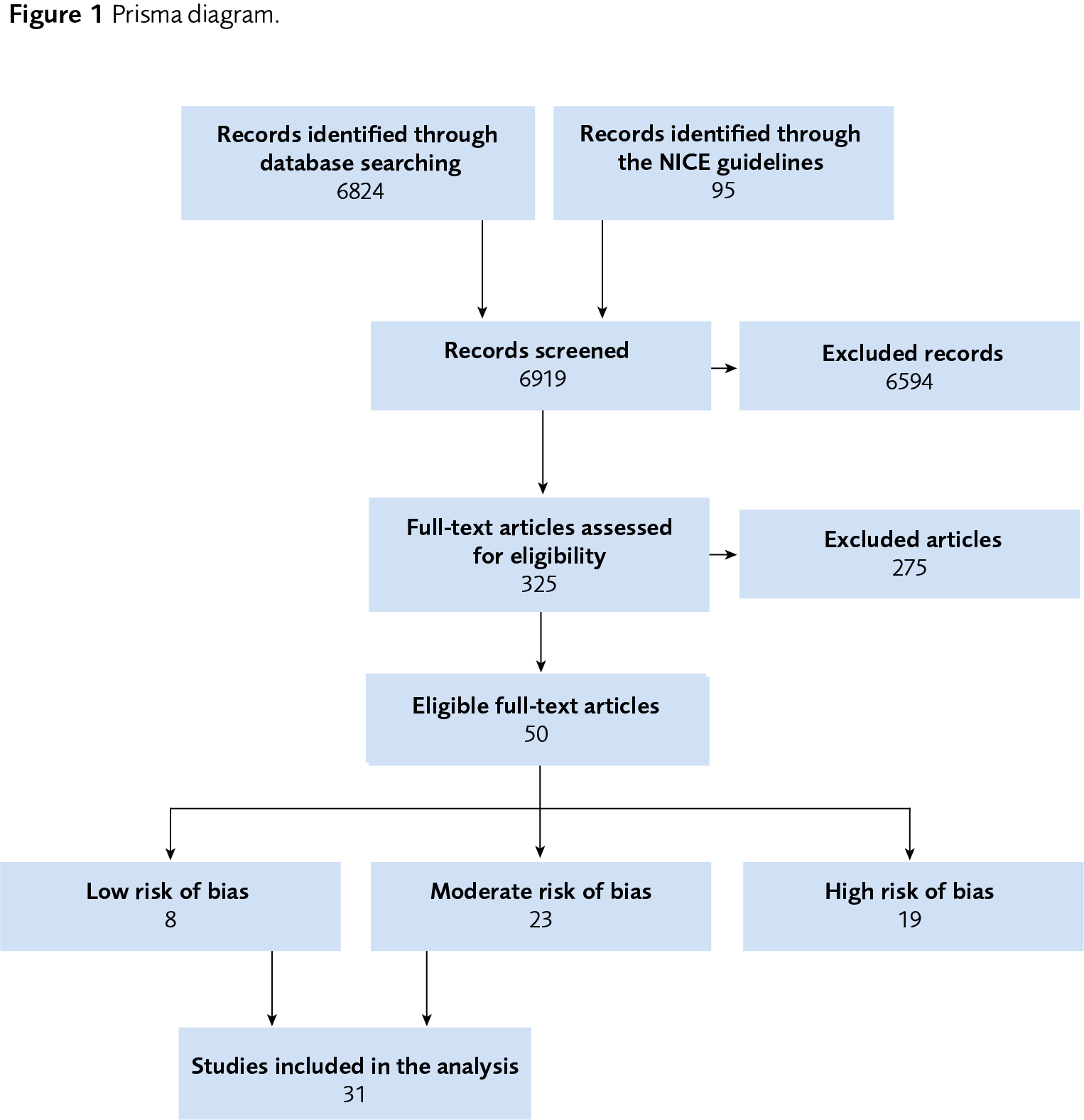

Thirty-one primary research articles are included in this systematic review (Figure 1). Three are included in review question 1, eight in review question 2, and 20 in review question 3.

| na = Not available in the published article; MD = Mean difference; SMD = Standardized mean difference. * 2 VAS 1–100: How do you feel right now about the approaching birth? From calm to worried and from no fear to strong fear. ** Results are calculated from values given in the original article in order to get confidence intervals which were not reported in the original publication. *** On a scale from 0 to 10: How afraid are you of childbirth? |

||

| Method/ intervention and population | Summary of results No. of participants (No. of studies); Effect (95% CI) Assessed effect size |

Certainty of evidence |

| Identification of fear of childbirth | Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) can be used to identify pregnant women with a fear of childbirth that needs to be further assessed. FOBS*: n=1383 (1); At cut-off FOBS≥54: sensitivity** = 85% (75% to 93%), specificity** = 80% (78% to 82%) VAS***: n=1348 (1); At cut-off VAS≥5: sensitivity = 98% (na), specificity = 66% (na); At cut-off VAS≥6: sensitivity = 89% (na), specificity = 76% (na) |

⊕⊕◯◯ Low |

| Interventions for fear of childbirth | Because the certainty of evidence is very low, the effect of interventions to treat fear of childbirth could not be estimated. | ⊕◯◯◯ Very low |

| Counselling for depression, anxiety disorders, or both | No studies were identified investigating the effect of counselling for any outcome | – |

| Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety disorders, or both | Psychoeducation can reduce depressive symptoms (assessed by screening instruments) in pregnant women with depression, anxiety disorders or both. N=557 (3); MD=–1.51 (–2.61 to –0.42) on EPDS (min=0; max=30; higher = worse; minimal reliable change = 4). We estimate the effect to be too small to be clinically relevant. |

⊕⊕◯◯ Low |

| Because the certainty of evidence is very low, the effect of psychoeducation on depressive symptoms (assessed by symptom rating scales), diagnosis of depression, state anxiety, or quality of life could not be estimated. | ⊕◯◯◯ Very low |

|

| No studies were identified investigating the effect of psychoeducation on trait anxiety or specific anxiety diagnoses. | – | |

| CBT for depression | CBT can reduce depressive symptoms in depressed pregnant women. N=132 (3); SMD=–0.87 (–1.25 to –0.48); With a standard deviation of 8.26, the effect corresponds to –7.15 (–10.35 to –3.95) on BDI-II (min=0; max=63; higher = worse; minimal reliable change = 6) We estimate the effect to be clinically relevant and moderate in size. |

⊕⊕◯◯ Low |

| CBT can reduce state anxiety in depressed pregnant women. N=196 (2); SMD=–0.75 (–1.20 to –0.31); With a standard deviation of 7.62, the effect corresponds to –5.74 (–9.14 to –2.34) on BAI (min=0; max=63; higher = worse; minimal reliable change = 11) We estimate the effect to be too small to be clinically relevant. |

⊕⊕◯◯ Low |

|

| Because the certainty of evidence is very low, the effect of CBT on depressive symptoms (assessed by screening instruments), diagnosis of depression, and quality of life could not be estimated. | ⊕◯◯◯ Very low |

|

| No studies were identified investigating the effect of CBT on trait anxiety or specific anxiety diagnoses. | – | |

| CBT for depression and anxiety disorders Behavioral activation for depression, anxiety disorders, or both Mindfulness for depression, anxiety disorders, or both |

Because the certainty of evidence is very low, the effect of CBT, behavioral activation or mindfulness on symptoms of depression or anxiety could not be estimated. | ⊕◯◯◯ Very low |

| No studies were identified investigating the effect of CBT, behavioral activation or mindfulness on diagnosis of depression or anxiety, trait anxiety, or quality of life. | – | |

| IPT for depression, anxiety disorders, or both | Because of very low certainty of evidence, the effect of IPT on diagnosis, symptoms of depression, or state anxiety could not be estimated. | ⊕◯◯◯ Very low |

| No studies were identified investigating the effects of IPT on trait anxiety, anxiety related diagnosis, or quality of life. | – | |

| PDT for depression, anxiety disorders, or both | No studies were identified investigating the effect of PDT for any outcome. | – |

Health Economic Assessment

It was not possible to assess the cost-effectiveness of treatments for fear of childbirth or mild to moderate anxiety and depression during pregnancy. Two studies were identified that evaluated psychoeducation compared with usual care, one for fear of childbirth and one for anxiety and depression during pregnancy. To assess health economic aspects studies of treatment effects and resource consumption are needed, as well as longer timeframes to capture all relevant effects.

Ethics

In summary, the ethical considerations identified concerns about the availability of effective care and the risk of unequal care due to stigmatization or lack of continuity and collaboration within the health care system. Regarding fear of childbirth, ethical considerations also concern the heterogeneity of the condition. It would be ethically problematic if the condition is seen as homogeneous and thereby prevent relevant adaptations of the treatment.

Discussion

If visual analogue scales are used to identify pregnant women with fear of childbirth, further assessment will be needed. These tests are better at identifying people with severe fear of childbirth than at excluding people without significant fear (sensitivity 85–98%, specificity 65–80%). The studies do not provide any guidance on how the assessment scales should be designed, nor what threshold would be suitable to detect clinically relevant levels of fear of childbirth.

For the treatment of fear of childbirth, specific treatment studies are needed for pregnant women with clinically relevant levels of fear of childbirth. Treatment studies are also needed that take into account the causes and the subject of the fear.

More studies are needed on interventions for depression and anxiety disorders during pregnancy. The existing studies are heterogenous, both regarding the intervention content and the population characteristics. The study populations are, in most studies, a mix of women with depression, anxiety, or both. Subgroup analyses could further the understanding of the treatment effects for the different conditions.

Conflicts of Interest

In accordance with SBU’s requirements, the experts and scientific reviewers participating in this project have submitted statements about conflicts of interest. These documents are available at SBU’s secretariat. SBU has determined that the conditions described in the submissions are compatible with SBU’s requirements for objectivity and impartiality.

The full report in Swedish

The full report "Förlossningsrädsla, depression och ångest under graviditet" (in Swedish)

Project group

Experts

- Ann Josefsson, MD, PhD, Professor in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Linköping University Hospital

- Marie Bendix, PhD, Consultant Psychiatrist, Psychiatry Southwest, Stockholm Region (SLSO)

- Ida Flink, Phd, Associate Professor, Licenced Psychologist, Örebro University

- Christina Nilsson, RNM, PhD, Associate Professor in Sexual and Reproductive Health, Faculty of Caring Science, Work Life and Social Welfare, University of Borås, Sweden

- Christine Rubertsson, Professor in Reproductive, Perinatal and Sexual Health, Lund University

- Lars Sandman, Professor in Health Care Ethics, Linköping University.

- Gunilla Sydsjö, Professor, Certified Psychotherapist, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital Linköping

SBU

- Nathalie Peira, Project Manager

- Naama Kenan Modén (Assistant Project Manager)

- Caroline Jungner (Project Administrator)

- Jenny Berg (Health Economist)

- Maja Kärrman Fredriksson (Information Specialist)

External reviewers

- Gerhard Andersson, Professor in Clinical Psychology, Linköping University

- Inger Lindberg, Associate Professor at the Department of Nursing, Umeå University

Flow chart

Reference list of the full report

- SFOG. Barnafödande och psykisk sjukdom. Svensk förening för obstetrik och gynekologi arbets- och referensgrupp för psykosocial obstetrik och gynekologi samt sexologi (SFOG); 2009. Rapport nr 62.

- O'Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger ML, Coppola E, Gaynes BN. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;321(6):588-601.

- SBU. Förebyggande av depression under graviditet och efter förlossning. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. SBU-rapport nr 4.

- Larkin P, Begley CM, Devane D. Women's experiences of labour and birth: an evolutionary concept analysis. Midwifery. 2009;25:e49-59.

- Graviditetsregistret. Årsredovisning 2019. 2020. Hämtad från graviditetsregistrets-aarsrapport-2019_20.pdf (sfog.se) den 2 februari 2021.

- O'Connell MA, Leahy-Warren P, Khashan AS, Kenny LC, O'Neill SM. Worldwide prevalence of tocophobia in pregnant women: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:907-20.

- Nilsson C, Hessman E, Sjoblom H, Dencker A, Jangsten E, Mollberg M, et al. Definitions, measurements and prevalence of fear of childbirth: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:28.

- Ternstrom E, Hildingsson I, Haines H, Rubertsson C. Higher prevalence of childbirth related fear in foreign born pregnant women--findings from a community sample in Sweden. Midwifery. 2015;31:445-50.

- Dencker A, Nilsson C, Begley C, Jangsten E, Mollberg M, Patel H, et al. Causes and outcomes in studies of fear of childbirth: A systematic review. Women Birth. 2019;32:99-111.

- Ryding EL, Persson A, Onell C, Kvist L. An evaluation of midwives' counseling of pregnant women in fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:10-7.

- SFOG. Förlossningsrädsla. Svensk förening för obstetrik och gynekologi arbets- och referensgrupp för psykosocial obstetrik och gynekologi samt sexologi (SFOG); 2017. ARG-rapport nr 77.

- Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Gissler M, Halmesmaki E, Saisto T. Mental health problems common in women with fear of childbirth. BJOG. 2011;118:1104-11.

- Rondung E, Thomten J, Sundin O. Psychological perspectives on fear of childbirth. J Anxiety Disord. 2016;44:80-91.

- Soderquist J, Wijma K, Wijma B. Traumatic stress in late pregnancy. J Anxiety Disord. 2004;18:127-42.

- Soderquist J, Wijma B, Wijma K. The longitudinal course of post-traumatic stress after childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;27:113-9.

- Ayers S BR, Bertullies S, Wijma K. The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: a meta-analysis and theoretical framework. . Psychological Medicine. 2016;46:1121-34.

- Larsson B, Karlstrom A, Rubertsson C, Hildingsson I. The effects of counseling on fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:629-36.

- Sydsjö G AL, Palmquist S, Bladh M, Sydsjö A, Josefsson A. Secondary fear of childbirth prolongs the time to subsequent delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013 Feb:210-4.

- Waldenstrom U, Hildingsson I, Rubertsson C, Radestad I. A negative birth experience: prevalence and risk factors in a national sample. Birth. 2004;31:17-27.

- Richens Y, Smith DM, Lavender DT. Fear of birth in clinical practice: A structured review of current measurement tools. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;16:98-112.

- Pallant H. Assessment of the dimensionality of the Wijma delivery expectancy/experience questionnaire using factor analysis and Rasch analysis. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2016;16:361.

- Roosevelt L, Kane Low L. Exploring fear of childbirth in the United States through a qualitative assessment of the Wijma delivery expectancy questionnaire. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2016;45:28-38.

- Cohen LS, Nonacs RM, Oldham JM, Riba MB, editors. Mood and anxiety disorders during pregnancy and postpartum. American Psychiatric Publishing. 2005;24.

- Mattisson C, Bogren M, Nettelbladt P, Munk-Jorgensen P, Bhugra D. First incidence depression in the Lundby Study: a comparison of the two time periods 1947-1972 and 1972-1997. J Affect Disord. 2005;87:151-60.

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593-602.

- Josefsson A, Berg G, Nordin C, Sydsjo G. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in late pregnancy and postpartum. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:251-5.

- Rubertsson C, Borjesson K, Berglund A, Josefsson A, Sydsjo G. The Swedish validation of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) during pregnancy. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65:414-8.

- Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, Whiteford HA, Harris MG. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:86-92.

- Häggström L, Reis M, editors. När kroppen är gravid och själen sjuk. Aktuell kunskap och praktisk handledning. Mölndal: Bokförlaget Affecta; 2009.

- NICE. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance Clinical guideline. Hämtad från https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192/evidence2014 [updated 11 February 2020 den 2 februari 2021.

- SFOG. Mödrahälsovård, Sexuell och Reproduktiv Hälsa. Svensk förening för obstetrik och gynekologi arbets- och referensgrupp för psykosocial obstetrik och gynekologi samt sexologi (SFOG); 2008, uppdaterad webbversion 2016. ARG rapport nr 76.

- Zoega H, Kieler H, Nörgaard M, Furu K, Valdimarsdottir U, Brandt L et al. Use of SSRI and SNRI antidepressans during pregnancy: a population-based study from Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. PLos One. 2015;10:e0144474.

- 33. Kammerer M, Marks MN, Pinard C, Taylor A, von Castelberg B, Kunzli H, et al. Symptoms associated with the DSM IV diagnosis of depression in pregnancy and post partum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:135-41.

- Nylen KJ, Williamson JA, O'Hara MW, Watson D, Engeldinger J. Validity of somatic symptoms as indicators of depression in pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16:203-10.

- SBU. Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården och insatser i socialtjänsten. En handbok. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2017.

- Rayyan QCRI. https://rayyan.qcri.org/.

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR, editors. Introduction to Meta‐Analysis: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009.

- Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. https://www.meta-analysis.com.

- McKenzie JE, Brennan SE. Chapter 12: Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Boutron I, Page MJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Lundh A, Hróbjartsson A. Chapter 7: Considering bias and conflicts of interest among the included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:231-40.

- Rikshandboken barnhälsovård för professionen. Available from www.rikshandboken-bhv.se/metoder--riktlinjer/screening-med-epds.

- Kernot J, Olds T, Lewis LK, Maher C. Test-retest reliability of the English version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18:255-7.

- 44. Matthey S. Calculating clinically significant change in postnatal depression studies using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:269-72.

- Morrell CJ , Warner R, Slade P, Dixon S, Walters S, Paley G et al. Psychological interventions for postnatal depression: cluster randomised trial and economic evaluation. The PoNDER trials. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13.

- FBanken. Formulärsammanställning. Available from www.fbanken.se.

- Button KS, Kounali D, Thomas L, Wiles NJ, Peters TJ, Welton NJ, et al. Minimal clinically important difference on the Beck Depression Inventory--II according to the patient's perspective. Psychol Med. 2015;45:3269-79.

- Hiroe T, Kojima M, Yamamoto I, Nojima S, Kinoshita Y, Hashimoto N et al. Gradations of clinical severity and sensitivity to change assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Japanese patients with depression. Psychiatry Res. 2005;135:229-35.

- Toussaint A, Husing P, Gumz A, Wingenfeld K, Harter M, Schramm E, et al. Sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7). J Affect Disord. 2020;265:395-401.

- Grade Working Group. Available from www.gradeworkinggroup.org.

- Storksen HT Eberhard-Gran M, Garthus-Niegel S, Eskild A. Fear of childbirth; the relation to anxiety and depression. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:237-42.

- Haines HM, Pallant JF, Fenwick J, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Toohill J, et al. Identifying women who are afraid of giving birth: A comparison of the fear of birth scale with the WDEQ-A in a large Australian cohort. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6(4):204-10.

- Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Halmesmaki E, Saisto T. Fear of childbirth according to parity, gestational age, and obstetric history. BJOG. 2009;116:67-73.

- Toohill J, Fenwick J, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Buist A, Turkstra E et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Psycho-Education Intervention by Midwives in Reducing Childbirth Fear in Pregnant Women. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care. 2014;41:384-94.

- Fenwick J, Toohill J, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Buist A, Turkstra E, et al. Effects of a midwife psycho-education intervention to reduce childbirth fear on women's birth outcomes and postpartum psychological wellbeing. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 2015;15:284.

- Toohill J CE, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Fenwick J. A cost effectiveness analysis of midwife psycho-education for fearful pregnant women - a health system perspective for the antenatal period. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 2017;17:217.

- Turkstra E, Mihala G, Scuffham PA, Creedy DK, Gamble J, Toohill J et al. An economic evaluation alongside a randomised controlled trial on psycho-education counselling intervention offered by midwives to address women's fear of childbirth in Australia. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2017;11:1-6.

- Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Toivanen R, Tokola M, Halmesmaki E, Saisto T. Life satisfaction, general well-being and costs of treatment for severe fear of childbirth in nulliparous women by psychoeducative group or conventional care attendance. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:527-33.

- Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Toivanen R, Tokola M, Halmesmaki E, Ryding EL, et al. Group psychoeducation with relaxation for severe fear of childbirth improves maternal adjustment and childbirth experience--a randomised controlled trial. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2015;36:1-9.

- Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Toivanen R, Tokola M, Halmesmaki E, Saisto T. Obstetric outcome after intervention for severe fear of childbirth in nulliparous women - randomised trial. BJOG. 2013;120:75-84.

- Saisto T, Salmela-Aro K, Nurmi JE, Kononen T, Halmesmaki E. A randomized controlled trial of intervention in fear of childbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:820-6.

- Trevillion K, Ryan E, Pickles A, Heslin M, Byford S, Nath S et al. An exploratory parallel-group randomised controlled trial of antenatal Guided Self-Help (plus usual care) versus usual care alone for pregnant women with depression. DAWN trial. 2020;1(187-97).

- Loughnan SA, Sie A, Hobbs MJ, Joubert AE, Smith J, Haskelberg H et al. A randomized controlled trial of ‘MUMentum Pregnancy’: Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy program for antenatal anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:381-90.

- Lund C, Schneider M, Garman EC, Davies T, Munodawafa M, Honikman S et al. Task-sharing of psychological treatment for antenatal depression in Khayelitsha, South Africa: Effects on antenatal and postnatal outcomes in an individual randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2019;1:103466.

- Khodakarami B, Bibalan FG, Soltani F, Soltanian A, Mohagheghi H. Impact of a Counseling Program on Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Spiritual Intelligence in Pregnant Women. Journal of Midwifery & Reproductive Health. 2017;5:858-66.

- McGregor M, Coghlan M, Dennis CL. The effect of physician-based cognitive behavioural therapy among pregnant women with depressive symptomatology: a pilot quasi-experimental trial. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2014;1:348-57.

- Milgrom J, Holt C, Holt CJ, Ross J, Ericksen J, Gemmill AW. Feasibility study and pilot randomised trial of an antenatal depression treatment with infant follow-up. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;1:717-30.

- Forsell E, Bendix M, Hollandare F, Szymanska von Schultz B, Nasiell J, Blomdahl-Wetterholm M et al. Internet delivered cognitive behavior therapy for antenatal depression: A randomised controlled trial. Affect Disord. 2017;1:56-64.

- Burns A, O’Mahen H, Baxter H, Bennert K, Wiles N, Ramchandani P, et al. A pilot randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for antenatal depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;1:33.

- Burger H VT, Aris-Meijer JL, Beijers C, Mol BW, Hollon SD, et al. Effects of psychological treatment of mental health problems in pregnant women to protect their offspring: Randomised controlled trial. 1. 2019:7.

- Dimidjian S, Goodman SH, Sherwood NE, Simon GE, Ludman E, Gallop R et al. A pragmatic randomized clinical trial of behavioral activation for depressed pregnant women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;1:26-36.

- Zemestani M, Fazeli Nikoo Z. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for comorbid depression and anxiety in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2019;1.

- Vieten C, Astin J. Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention during pregnancy on prenatal stress and mood: results of a pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:67-74.

- Yang M, Jia G, Sun S, Ye C, Zhang R, Yu X. Effects of an Online Mindfulness Intervention Focusing on Attention Monitoring and Acceptance in Pregnant Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64:68-77.

- Guardino CM, Dunkel Schetter C, Bower JE, Lu MC, Smalley SL. Randomised controlled pilot trial of mindfulness training for stress reduction during pregnancy. Psychol Health. 2014;1:334-49.

- Field T, Diego M, Delgado J, Medina L. Peer support and interpersonal psychotherapy groups experienced decreased prentatal depression, anxiety and cortisol. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:621-4.

- Spinelli MG, Endicott J, Leon AC, Goetz RR, Kalish RB, Brustman LE et al. A controlled clinical treatment trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed pregnant women at 3 New York City sites. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:393-9.

- Lenze SN, Pptts MA. Brief Interpersonal Psychotherapy for depression during pregnancy in a low-income population: A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2017;1:151-7.

- Grote NK, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Lohr MJ, Curran M, Galvin E et al. A Randomized Trial of Collaborative Care for Perinatal Depression in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Women: The Impact of Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;1:1527-37.

- Grote NK, Swartz HA, Geibel SL, Zuckoff A, Houck PR, Frank E. A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(3):13-21.

- Grote NK Katon WJ, Russo JE, Lohr MJ, Curran M, Galvin E, et al. Collaborative care for perinatal depression in socioeconomically disadvantaged women: a randomized trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;1:821-34.

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG (editors). Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Nieminen K, Wijma K, Johansson S, Kinberger EK, Ryding EL, Andersson G et al. Severe fear of childbirth indicates high perinatal costs for Swedish women giving birth to their first child. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:438-46.

- Socialstyrelsen. Prospektiva viker för slutenvårds- och öppenvårdsgrupper i psykiatrisk vård, NordDRG 2021. 2020. Available from Viktlistor för NordDRG - Socialstyrelsen.

- Bauer A, Knapp M, Parsonage M. Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:83-90.

- Socialstyrelsen. Vård efter förlossning. En nationell kartläggning av vården till kvinnor efter förlossning. 2017. ISBN 978-91-7555-420-4.

- SKL. Trygg hela vägen. Kartläggning av vården före, under och efter graviditet. Stockholm: Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting (SKL); 2018. ISBN: 978-91-7585-620-9.

- Goodman JH. Women's attitudes, preferences, and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth. 2009;36:60-9.

- O'Mahen HA, Flynn HA. Preferences and perceived barriers to treatment for depression during the perinatal period. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17:1301-9.

- Stoll K, Swift EM, Fairbrother N, Nethery E, Janssen P. A systematic review of nonpharmacological prenatal interventions for pregnancy-specific anxiety and fear of childbirth. Birth. 2018;45:7-18.

- Moghaddam Hosseini V, Nazarzadeh M, Jahanfar S. Interventions for reducing fear of childbirth: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Women Birth. 2018;31:254-62.

- SBU. Vad är viktigt att mäta i forskning som undersöker behandling av depression under och efter graviditet? Framtagande av ett Core Outcome Set. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. SBU-rapport nr 314. ISBN 978-91-88437-56-3.

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Share via Email