Caesarean section on maternal request

A systematic review and assessment of medical, health economic, ethical and social aspects

Conclusions

Results from studies with quantitative methodology (complications):

- For the mother, there are risks for complications after both vaginal delivery and caesarean section, both in the short and long term. If also risks of complications during subsequent births are included, then the complications after caesarean section are somewhat more numerous and potentially more serious than after vaginal delivery. It should be noted, however, that serious complications are rare (Table 1).

- Examples of complications with increased risk following planned caesarean section without medical indication compared to planned vaginal delivery are infections, excessive bleeding, pulmonary embolism after birth, that the uterus ruptures or the placenta grows into the uterine wall at a subsequent delivery (all high certainty of evidence) and ileus in the long term after birth (moderate certainty of evidence).

- Examples of complications with lowered risk following caesarean section are complications that affect perineal function. In the short term, this includes anal sphincter injury (high certainty of evidence) and, in the long term, urinary stress incontinence (moderate certainty of evidence) and need for surgery due to pelvic floor problems (low certainty of evidence).

- For the child, there are slightly to moderately increased risks for complications with a planned caesarean section, if a medical indication is missing, compared to a planned vaginal delivery, both in the short and long term (Table 1). No lowered risks for the child after caesarean section without medical indication were found in the included studies.

- Examples of complications with increased risk after caesarean section are admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), that the child suffers from respiratory morbidity after birth, and that the child develops asthma (moderate certainty of evidence) or diabetes during childhood (low certainty of evidence).

Results from studies with qualitative methodology (perceptions and experiences):

- Women who request a caesarean section without medical indication regarded caesarean section as being associated with lower risks than vaginal birth, while healthcare staff who meet these women held the opposite view (moderate certainty of evidence).

- The women considered themselves to have a right to demand a caesarean section, while the healthcare staff they meet had widely varying views regarding to what extent the woman has a right to choose the mode of delivery herself (moderate certainty of evidence).

- The women found it most important to get acceptance for their request for caesarean section, while the staff rather highlighted the importance of different types of support, as well as time for discussion and to treat the women with respect and understanding (moderate certainty of evidence).

- Healthcare staff thought that the high workload in the delivery units can complicate deliveries, result in negative birth experiences, limit the possibility of follow-up after delivery and thus lead to future requests for caesarean section (moderate certainty of evidence).

Health economic results:

Health economic model analyses for Sweden that we conducted based on the results for the risk comparison between the two methods of birth, Swedish cost data and quality of life weights from the literature show:

- For primiparous women, the costs of birth and hospital care during the subsequent year are on average between 26 000 and 32 000 Swedish crowns higher per planned caesarean section without medical indication compared to planned vaginal birth in Sweden. For multiparous women, the cost increase lies between 29 000 and 36 000 Swedish crowns per planned caesarean section without medical indication. These results include costs for method of delivery and hospital costs for short-term complications for both mother and child.

- Planned vaginal delivery leads to lower costs for hospital care and somatic health gains compared to planned caesarean section without medical indication, also with a longer perspective of up to 20 years. The analyses consider costs for the method of delivery, hospital care costs for short- and long-term complications for mother and child, as well as the impact on quality of life of long-terms complications for mother and child. Although there are uncertainties around for example quality of life effects, the overall result remains unchanged in sensitivity analyses.

- The overall budget impact for somatic care of planned caesarean section in women without medical indication is estimated to between 75 and 93 million Swedish crowns per year in Sweden, based on a healthcare perspective with a focus on hospital costs.

Background

Following a large increase in the number of caesarean sections until the year 2006 in Sweden, the share of caesarean sections has been stable around 18 percent. Around half of these are planned caesarean sections, most of them with various medical indications, and half are acute caesarean sections. The largest group of women who request a caesarean section without medical indication are multiparous women. There is a lack of a national consensus around what is to be considered as a caesarean section on maternal request, which means that statistics on this is uncertain. Amongst primiparous women, approximately 1-2 percent of births are caesarean sections on maternal request. Amongst multiparous women, this number is approximately 3- 7 percent, depending on whether one includes caesarean sections where no clear medical indication is given.

Clinical practice in Sweden varies widely between maternity clinics and regions, as do the number of planned caesarean sections, and planned caesarean sections on maternal request. Written guidelines for planned caesarean sections are missing at most maternity clinics.

Aim

The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the somatic risks for mother and child of a caesarean section on maternal request without medical indication, to perform a qualitative analysis of perceptions and experiences amongst women and healthcare staff, to conduct health economic analyses, and to discuss ethical aspects.

Method

Systematic reviews were conducted in accordance with the international PRISMA guidelines and SBU’s methods handbook for quantitative and qualitative studies. Moreover, health economic and ethical aspects were assessed.

For the questions regarding risks for maternal complications with a caesarean section on maternal request in the short-term and following a prior caesarean section, recent reports by the National Board of Health and Welfare using national registry data were deemed sufficient. Thus, no further literature search was performed for these outcomes.

The certainty of the results was assessed using GRADE (Question 1, results of studies using quantitative methodology) and GRADE-CERQual (Questions 2 and 3, results of studies using qualitative methodology), respectively. Statistics from the report by the National Board of Health and Welfare and the Medical Birth Registry were used as sources for the practice survey.

For the assessment of health economic aspects, the results of the systematic review of complication risks with different delivery methods were used, when the results were deemed to be of low, moderate or high certainty. National and regional registry data were used for healthcare costs. We constructed a health economic model that weighs together the results regarding risks for mother and child and relates these to costs and impact on quality of life. The calculated costs after one year were used to estimate the budget impact on hospitalisation costs in Sweden.

Ethical, social, and societal aspects were illustrated through discussions in the project team, partly based on questions from SBU’s ethical guideline for healthcare.

The protocol was registered in Prospero.

Inclusion criteria (PICOs)

Question 1: What are the risks and benefits for mother and child with a caesarean section on maternal request without medical indication compared to vaginal delivery?

Population

Pregnant women, mothers, new-borns and children.

Intervention

Caesarean section on maternal request. Since existing registers not always contain information on whether a caesarean section happens on maternal request, planned caesarean sections without medical indication (for long-term maternal complications: all types of caesarean sections, including acute ones) were considered to be the same as caesarean sections on maternal request. It was required for the study results to be adjusted for potential confounders, which could have contributed to a decision to perform a caesarean section. This was assessed, amongst other instances, as part of the evaluation of risk of bias.

Control

Primarily planned vaginal delivery. Secondarily, all types of vaginal deliveries. For short-term complications for the child, a comparison with planned vaginal delivery was required.

Outcomes

Mother:

- Short-term complications, within 6 weeks after delivery.

- Complications at subsequent delivery, after prior caesarean section.

- Long-term complications, more than 1 year after delivery.

Child:

- Short-term complications, within 28 days after birth, including perinatal/neonatal death.

- Complications at subsequent delivery when the mother has had a prior caesarean section without medical indication.

- Long-term complications, more than 1 year after birth.

All complications deemed to be clinically relevant for mother or child were included.

Examples of outcomes that were excluded on this basis were results of a basic research nature, such as plasma levels of hormones, cytokines, and gene expression.

Study design

Randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies with control group published in peer-reviewed journals.

Exclusion criteria

Multiple births and prematurity, and studies focusing on pregnant women/mothers with chronic diseases such as diabetes, rheumatoid diseases, cancer etc.

The project was restricted to somatic risks for the mother and child. Outcome measures for different forms of mental ill-health were excluded due to often ambiguous definitions in the field, considerable problems with confounders, and difficulties of following up in existing registries how women’s wishes are handled.

Language

English, Swedish, Danish, or Norwegian.

Search period

From 2000 to 2021. Final search May 2021.

Databases searched

Final searches in Embase via Elsevier, Ovid MEDLINE, Scopus via Elsevier. Initial searches in Cochrane Library, CRD databases: DARE; HTA Database, NHS EED, Evidence Search (NICE) International HTA Database, KSR Evidence and Prospero, as well as CINAHL via EBSCO, Ovid Medline and PsycInfo.

Client/patient involvement

No.

Question 2: What perceptions do women who express a wish for a caesarean section have about different methods of birth? What experiences do women have of their participation in the decision and the reception by healthcare staff when expressing a desire for caesarean section?

Question 3: What perceptions and experiences do healthcare staff have when women express a desire for a caesarean section and the healthcare staff find that a medical indication is missing?

Population

Women who approach the healthcare system with a desire for caesarean section. Healthcare staff who handle these requests.

Setting

All types of settings.

Outcomes

Perceptions and experiences of the meeting between healthcare staff and pregnant women who desire or have requested a caesarean section without medical indication. Attitudes and perceptions that are important for the experience of the meeting/meetings. Limitation: Reasons for request for caesarean section when there is no medical indication.

Study design

Studies with qualitative methodology published in peer-reviewed journals.

Language

English, Swedish, Danish, or Norwegian.

Search period

From 2000 to 2021. Final search May 2021.

Databases searched

Final searches in CINAHL via EBSCO, Ovid MEDLINE, PsycInfo via EBSCO and Scopus via Elsevier. The database SveMed+ was checked. Initial searches in Cochrane Library, CRD databases: DARE; HTA Database, NHS EED, Evidence Search (NICE) International HTA Database, KSR Evidence and Prospero, as well as CINAHL via EBSCO, Ovid Medline and PsycInfo.

Client/patient involvement

No.

Results

Results from studies using quantitative methodology (Complications)

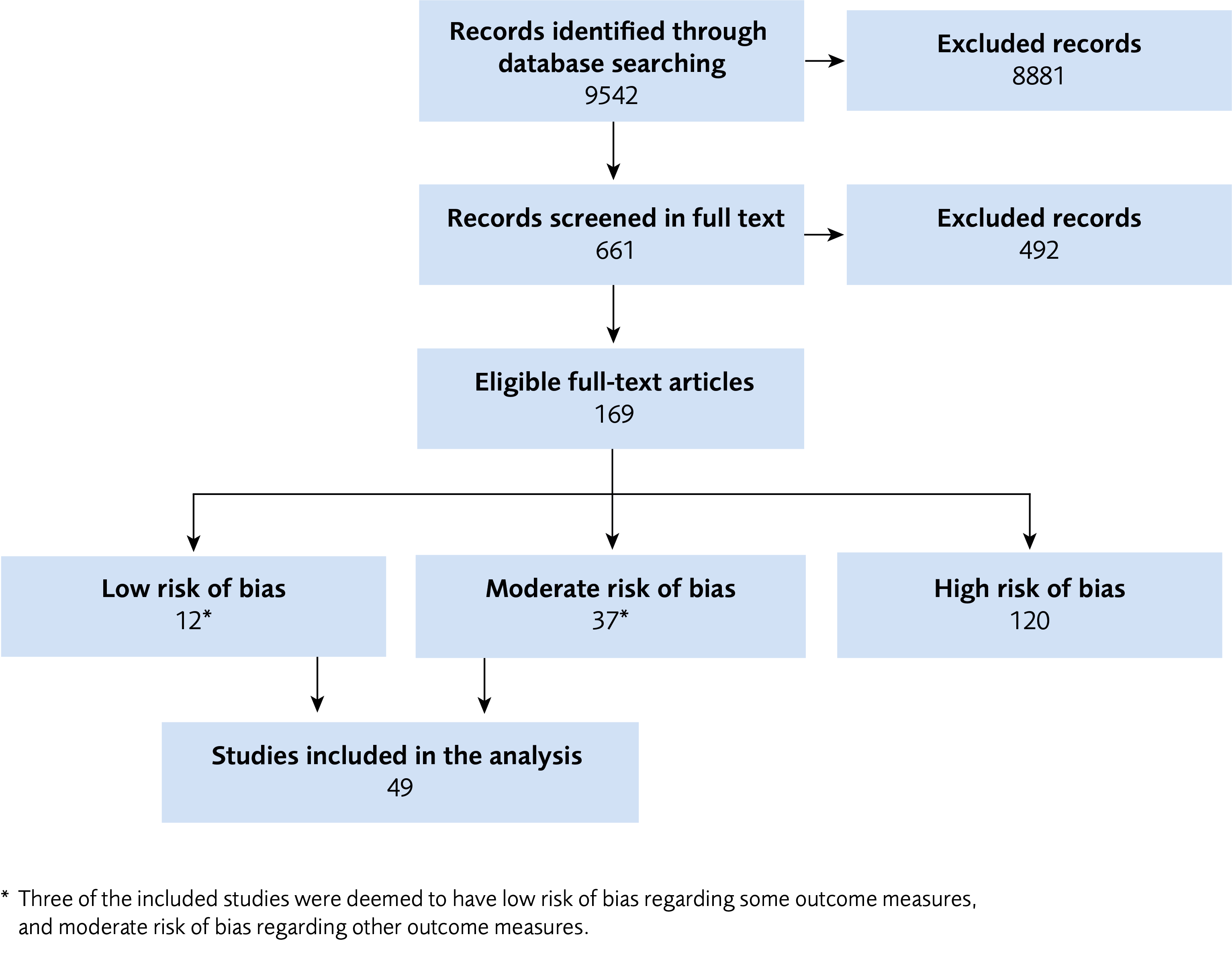

We found no relevant randomised studies. The results are based on 49 non-randomised studies with control group, mainly registry studies with the aim to study the risks of planned caesarean section without medical indication compared to vaginal birth in a population of women with low risk (see Figure 1). The results in the included studies have been adjusted for potential confounders that may have contributed to a decision to perform a caesarean section based on an inherent difference between the groups. For maternal long-term complications, we included results for all types of caesarean sections, both acute and planned, the latter regardless of whether medical indications were present or not.

Overall, 12 outcomes showed an increased risk for the mother with caesarean section, compared to vaginal delivery, and six outcomes showed a lowered risk for the mother. For the child, 11 outcomes showed an increased risk with planned caesarean section compared to vaginal birth. No outcomes showed a lowered risk for the child with planned caesarean section compared to vaginal birth (Table 1). Results with very low certainty of evidence have not been included in the table below.

| a Adhesions: Tissues connecting organs or organ to abdominal wall. This can lead to various consequences from no symptoms to serious complications like infertility or ileus. b N/A: Not applicable. The risk for anal sphincter injury after caesarean section with medical indication can be set to zero. A relative risk estimate can therefore not be calculated. The risk for anal sphincter injury following caesarean section with medical indication is about 2.9 % (NNT = 34). c Pelvic floor surgery: Includes surgery of all types of pelvic floor problems like prolapse, urinary and anal incontinence. d Breathing disorder: Often denoted respiratory morbidity in the included studies, including various types of breathing disorders from mild to severe, which also may need respiratory support and oxygen treatment. e Low Apgar score (<7 at 5 minutes): A scoring system which describes the new-born’s status at 5 minutes after birth (0–10 points). Low Apgar score is associated with future morbidity. f Treatment of respiratory tract infection in hospital: Majority of children below 2 years of age. 95 % CI = 95% confidence interval; NNH = Number Needed to Harm. The number of individuals who have to be exposed to a caesarean section to result in one extra case of the complication compared with vaginal delivery. Higher value means smaller absolute risk difference and less frequent complication; NNT = Number Needed to Treat. The opposite to NNH, number of individuals to be exposed to result in one fewer complication. Relative risk: A ratio between the risk for a complication after a caesarean section divided by the risk for the same complication after vaginal delivery. A relative risk of 0.8 means a relative risk reduction of 20 %. Certainty of evidence: ⊕⊕⊕⊕ = High certainty: The result can be seen as correct. ⊕⊕⊕◯ = Moderate certainty: The result is probably correct. ⊕⊕◯◯ = Low certainty: It is possible that the result is correct. *) The outcomes and comparisons in the report are grouped as follows:

|

||||

| Time period | Increased risk for woman (follow-up) | Certainty of evidence according to GRADE | NNH | Relative risk (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During or short time after childbirth (up to 6 weeks) | Excessive bleeding | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 10 | 6.18 (6.00–6.37) |

| Pulmonary embolism | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 2300 | 1.72 (1.38–2.14) |

|

| Infection in uterus | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 480 | 1.12 (1.07–1.19 |

|

| Urinary tract infection | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 340 | 1.41 (1.32–1.52) |

|

| Wound infection | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 90 | 2.60 (2.47–2.75) |

|

| Milk congestion | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 80 | 1.53 (1.48–1.59) |

|

| Antibiotic treatment | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 30 | 1.33 (1.31–1.36) |

|

| Next pregnancy | Growth of placenta into uterine wall | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 3500 | 10.9 (8.4–14.0) |

| Next childbirth | Uterine rupture | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 190 | 24.4 (22.8–26.0) |

| Long time after childbirth (follow-up time) | Surgery for abdominal adhesionsa (25 years) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 130 | 2.8 (2.6–3.1) |

| Ileus surgery (12 years) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 450 | 2.25 (2.15–3.0) |

|

| Surgery for abdominal wall hernia (25 years) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 80 | 3.2 (3.0–3.4) |

|

| Time period | Reduced risk for woman | Certainty of evidence according to GRADE | NNT | Relative risk (95 % CI) |

| During or short time after childbirth | Anal sphincter injury | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 30 | N/Ab |

| Long time after childbirth (follow-up time) | Prolapse symptoms (20 years) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 60 | 0.52 (0.28–0.99) |

| Prolapse surgery (25 years) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 70 | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) |

|

| Stress incontinence symptoms (10 years) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 10 | 0.42 (0.31–0.59) |

|

| Stress incontinence surgery (25 years) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 150 | 0.3 (0.2–0.3) |

|

| Pelvic floor surgeryc (20 years) | ⊕⊕◯◯ | 460 | 0.68 (0.51–0.90) |

|

| Time period | Increased risk for child | Certainty of evidence according to GRADE | NNH | Relative risk (95 % CI) |

| Short time after childbirth | Breathing disorderd | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 70 | 2.02 (1.49–2.73) |

| Transfer to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 20 | 1.92 (1.44–2.56) |

|

| Next childbirth | Next child after previous caesarean section Apgar score <7 at 5 minutese | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 180 | 1.60 (1.50–1.71) |

| Infant years | Treatment of respiratory tract infection in hospitalf | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 130 | 1.14 (1.09–1.19) |

| Toddler years | Gastrointestinal tract infections requiring hospital care | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 130 | 1.21 (1.16–1.25) |

| Childhood | Asthma | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 120 | 1.19 (1.17–1.21) |

| Food allergy | ⊕⊕◯◯ | 260 | 1.16 (1.11–1.21) |

|

| Diabetes | ⊕⊕◯◯ | 1800 | 1.11 (1.04–1.17) |

|

| Overweight | ⊕⊕◯◯ | 100 | 1.17 (1.07–1.29) |

|

| Later in life | Inflammatory bowel disease | ⊕⊕◯◯ | 860 | 1.16 (1.03–1.30) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ⊕⊕⊕◯ | 1700 | 1.17 (1.06–1.28) |

|

| Time period | Reduced risk for child | Certainty of evidence according to GRADE | NNT | Relative risk (95 % CI) |

| – | – | – | – | – |

Results from studies using qualitative methodology (Perceptions and experiences)

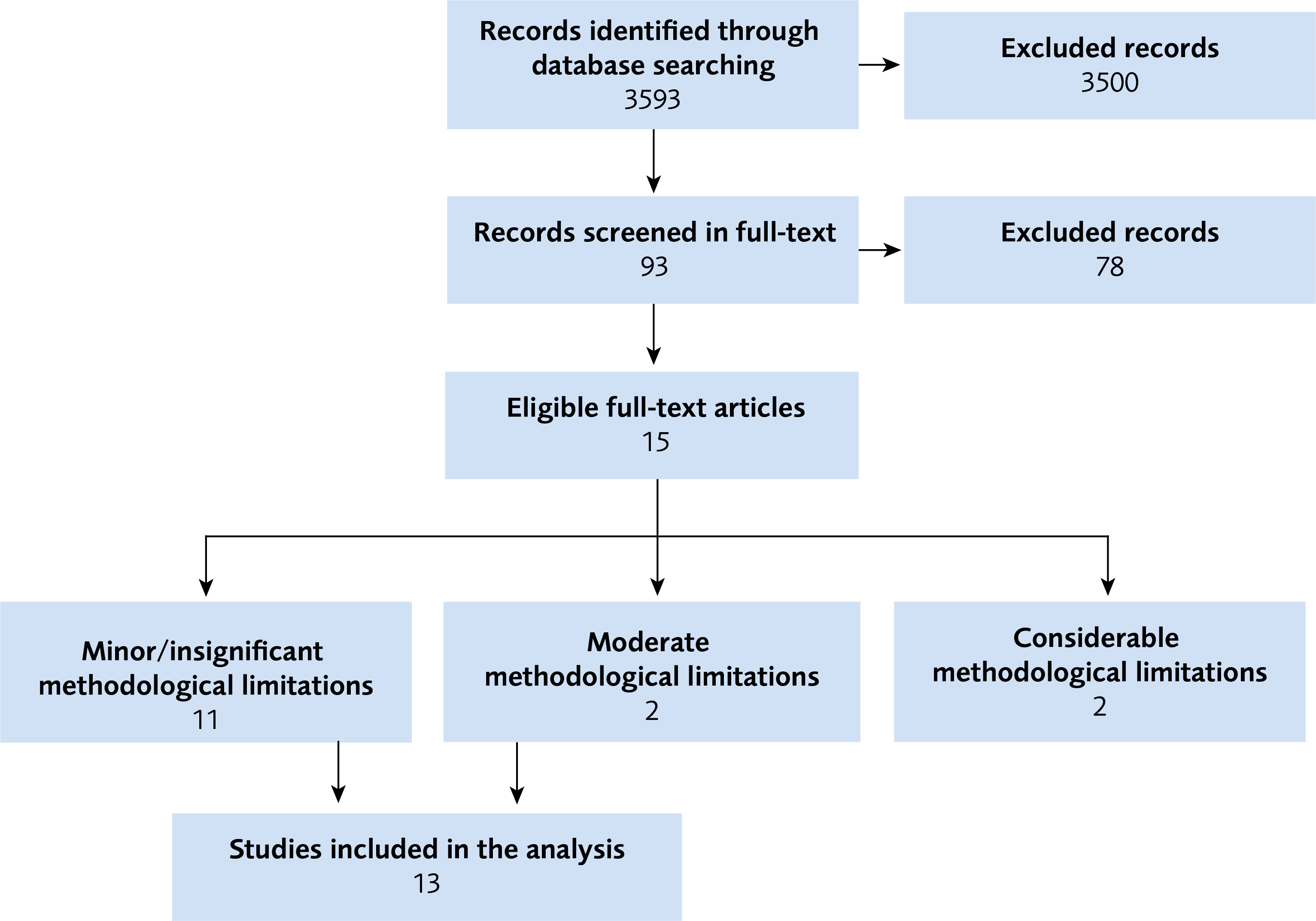

Relevant data from 13 included studies using qualitative methodology (Questions 2 and 3, see Figure 2) were summarised in two thematic syntheses, one for the women’s perspective and one for the healthcare staff’s perspective (Table 2).

When the statements of women and healthcare staff are compared, it becomes clear that they have differing views regarding:

- Risk: The women thought that caesarean section is a safer method of delivery compared to vaginal delivery, while the healthcare staff who meet these women think the opposite.

- Right to a caesarean section: The women considered it their right to receive a caesarean section if they so wish, while the healthcare staff who meet them had widely varying viewpoints regarding to what extent the woman has a right to choose the mode of delivery herself.

- Support: The healthcare staff thought that support for the woman means to meet her respectfully and with understanding, time for discussion, and guiding her to the best solution for her. The women thought that support primarily means that the healthcare staff accept their wish to receive a caesarean section.

In addition, healthcare staff thought that the high workload in maternity care can complicate deliveries, result in negative birth experiences, limit the possibility of follow-up after delivery and thus lead to future requests for caesarean section.

| Perspective of the women – themes level 3 (Certainty of evidence) | Perspective of the staff – themes level 3 (Certainty of evidence) |

|---|---|

| Risks and advantages with caesarean section The women requesting a caesarean section often regarded vaginal delivery as being associated with risks and caesarean section as a more predictable and controlled mode of delivery, associated with small or no risks. Potential risks were minimized or ignored. The women put their trust in the competence of the surgical team and handed over the responsibility for the delivery to them. After having experienced a caesarean section, however, the women could re-evaluate their view regarding risk. The women’s view of the information about risks they had been given varied, ranging from adequate, insufficient to contradictory. The health care staff’s acceptance of their preferred mode of delivery was more important to them than receiving information about risks. (Moderate certainty of evidence ⊕⊕⊕◯) |

View of risks The health care staff considered caesarean section to be associated with more risks than vaginal delivery. They expressed concerns regarding the increasing prevalence of caesarean sections and emphasized that when deciding upon mode of delivery, the woman needs to be informed about the consequences and risks associated with caesarean section. (Moderate certainty of evidence ⊕⊕⊕◯) |

| Support and acceptance of preferred mode of delivery The women considered it their right to gain acceptance of their preferred mode of delivery. Many of the women also received this acceptance. Sometimes, however, the women’s preference was rejected. Also, the women could regard the decision process considering mode of delivery as unserious with a lack of support. The women often had to repeat and defend their decision about mode of delivery, which they considered to be well motivated. Some women renegotiated their attitudes towards mode of delivery through experience of birth or professional support in the decision process. (Moderate certainty of evidence ⊕⊕⊕◯) |

Experiences of meeting women who request a caesarean section The health care staff viewed the women’s request for a caesarean section to be grounded in a misunderstanding regarding advantages and disadvantages concerning caesarean section, and that it was challenging to manage the requests. The staff also highlighted that the high workload in delivery units can complicate deliveries, result in negative birth experiences, limit the possibility of follow-up after delivery and thus lead to future requests for caesarean section. (Moderate certainty of evidence ⊕⊕⊕◯) |

| Factors that affect the decision about mode of delivery The health care staff had widely varying views regarding to what extent the woman has a right to choose the mode of delivery herself. Members of the staff also had different opinions regarding medical indications for caesarean section, including if fear of birth constitutes such an indication or not. The staff emphasized that evidence is an important basis for the decision, but also that factors such as the organization and capacity of the health care system affected the decision. (Moderate certainty of evidence ⊕⊕⊕◯) |

|

| Views upon how women requesting a caesarean section should be handled The healthcare staff considered it important to give the woman many different types of support, evidence-based information and time for dialogue early during the pregnancy, and to treat the women with respect and understanding and at the same time discuss alternatives to caesarean section. These measures were perceived as being able to enhance women’s ability to give birth and thus reduce the number of requests for, as well as the prevalence of, caesarean sections. (Moderate certainty of evidence ⊕⊕⊕◯) |

Health economic assessment

The health economic model analyses indicate that, in a Swedish context, planned vaginal birth is consistently cost saving and leads to long-term somatic health gains, compared to planned caesarean section without medical indication. Apart from the uncertainty around the relative risks for complications, there is uncertainty particularly regarding the duration of several long-term complications and their impact on quality of life. However, a range of sensitivity analyses indicate that the overall result remains stable when the input values are varied.

In this project, we have not analysed possible complications in terms of mental ill-health that are related to different methods of delivery. This means that we have not been able to include psychological aspects related to different methods of delivery, such as traumatic birth experiences, in our health economic model. There may be psychological aspects that influence the aggregated effect of planned caesarean section on maternal request compared to planned vaginal delivery. However, it is not possible to comment on the size of this effect based on our report.

The health economic model estimates cover direct medical costs, mostly focused on hospital care. This means that costs for outpatient care or due to reduced working ability are not included in the calculations. However, sensitivity analyses where yearly outpatient care costs are assumed for complications that are reduced with planned caesarean section indicate that this type of cost likely does not have any major impact on results.

Ethical and societal aspects

The presented results apply to planned caesarean section without medical indication. A planned caesarean section on maternal request without medical indication exposes the child to increased short- and long-term complications. Although the absolute risk increases often are small, this constitutes an ethical problem. Moreover, the fact that different maternity clinics and healthcare staff can handle women’s requests for caesarean section in different ways also constitutes an ethical problem, since it leads to unequal care.

Discussion

An argument that is sometimes put forward in favour of caesarean section concerns complications that can occur if the child gets stuck in the birth canal (for example clavicle fracture or nerve damage affecting the arms), and that these cannot occur with a planned caesarean section. According to data from the Swedish Medical Birth Registry, the risk of a child getting stuck with its shoulders is 1/350 (0.3 %) with planned vaginal delivery for pregnancies that have lasted 39 weeks or more. In a Swedish context, there is an important knowledge gap regarding the consequences of a child getting stuck and more research is needed.

The women and healthcare staff had different views on caesarean section without medical indication and, furthermore, totally different expectations on what the meeting between them should result in. This is something that both the women and healthcare staff may need to prepare for. Moreover, these differences in views between the groups remain unchanged even after earlier pregnancies and deliveries. This indicates a need for better dialogue between healthcare staff and the women, foremost regarding the risks associated with different methods of delivery. Some of the included studies have a context that possibly differs from Swedish circumstances. This was handled as part of the assessment of the certainty of the results.

Caesarean section without medical indication leads to increased costs of care for the delivery and treatment of somatic complications, and there is a risk of displacement effects concerning other healthcare. However, we cannot comment on the psychological consequences associated with different methods of delivery in relation to the mother’s wishes, or how these impact on cost-effectiveness.

Conflicts of interest

In accordance with SBU’s requirements, the experts and scientific reviewers participating in this project have submitted statements about conflicts of interest. These documents are available at SBU’s secretariat. SBU has determined that the conditions described in the submissions are compatible with SBU’s requirements for objectivity and impartiality.

The full report in Swedish

The full report in Swedish Kejsarsnitt på kvinnans önskemål – fördelar och nackdelar för kvinna och barn

Project group

Experts

- Ellika Andolf (Professor Emerita)

- Cecilia Ekeus (Professor)

- Lena Hellström-Westas (Professor)

- Ingegerd Hildingsson (Professor)

- Margareta Johansson (Associate Professor)

- Karin Källén (Professor)

- Lars Sandman (Professor, ethics)

- Ulrik Kihlbom (Associate Professor, ethics)

SBU

- Sigurd Vitols (Project Manager)

- Jonatan Alvan (Project Manager)

- Maria Ahlberg (Project Administrator)

- Jenny Berg (Health Economist, from January 2021)

- Agneta Brolund (Information Specialist)

- Hanna Olofsson (Information Specialist)

- Johanna Wiss (Health Economist, until January 2021)

External reviewers

- Ann Josefsson (Professor)

- Ingela Lundgren (Professor)

- Thomas Davidson (Associate Professor, health economics)

Flow charts

Figure 1 Flow chart of studies with quantitative methodology.

Figure 2 Flow chart of studies with qualitative methodology.

Reference list of full report

- Medicinska födelseregistret.: Socialstyrelsen,. [accessed Oct 3 2021]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/register/alla-register/medicinska-fodelseregistret/.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

- SBU. Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården och insatser i socialtjänsten: en metodbok. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. [accessed Sep 20 2021]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/metodbok.

- GRADE. The GRADE working group. [accessed April 27 2021]. Available from: https://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/.

- GRADE-CERQual. The GRADE-CERQual Project Group. [accessed Sep 20 2021]. Available from: https://www.cerqual.org/.

- Kejsarsnitt i Sverige 2008-2017. Kriterier som styr beslut om förlossningssätt, samt kartläggning av komplikationer. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2019. [accessed Sep 20 2021]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2019-12-6529.pdf.

- SBU. Etiska aspekter på insatser inom hälso- och sjukvården. En vägledning för att identifiera relevanta etiska aspekter. In: Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården och insatser i socialtjänsten: en metodbok. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. [accessed 27 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/etiska_aspekter_halso_sjukvarden.pdf.

- Wiklund I, Malata AM, Cheung NF, Cadee F. Appropriate use of caesarean section globally requires a different approach. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1288-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32325-0.

- Indikation för kejsarsnitt på moderns önskan. Rapport 2011:09 från samarbetsprojektet Nationella medicinska indikationer. Stockholm: Svensk Förening för Obstetrik och Gynekologi (SFOG); 2011. [accessed Sep 20 2021]. Available from: https://www.sfog.se/media/336234/nationella-indikationer-kejsarsnitt-moderns-onskan.pdf.

- Gunnervik C, Josefsson A, Sydsjö A, Sydsjö G. Attitudes towards mode of birth among Swedish midwives. Midwifery. 2010;26(1):38-44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2008.04.006.

- Gunnervik C, Sydsjö G, Sydsjö A, Selling KE, Josefsson A. Attitudes towards cesarean section in a nationwide sample of obstetricians and gynecologists. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(4):438-44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340802001711.

- Rätten att välja kejsarsnitt. Privat medlemsgrupp på Facebook. [accessed Sep 20 2021]. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/groups/408540175823586/.

- Vi kräver en lex Rasha. 288 debattörer: Låt inte fler kvinnor dö när de föder barn. Stockholm: Aftonbladet; 2019. [accessed Sep 20 2021]. Available from: https://www.aftonbladet.se/debatt/a/mRpw1g/vi-kraver-en-lex-rasha.

- Judgement Montgomery (Appellant) v Lanarkshire Health Board (Respondent) (Scotland). 2015 SCLR 315. United Kingdom Supreme Court. [accessed Sep 20 2021]. Available from: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKSC/2015/11.html.

- Caesarean birth overview. London: NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. [accessed Aug 30 2021]. Available from: http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/caesarean-section

- Romanis EC. Why the Elective Caesarean Lottery is Ethically Impermissible. Health Care Anal. 2019;27(4):249-68. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-019-00370-0.

- Jenabi E, Khazaei S, Bashirian S, Aghababaei S, Matinnia N. Reasons for elective cesarean section on maternal request: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(22):3867-72. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2019.1587407.

- Nieminen K, Stephansson O, Ryding EL. Women's fear of childbirth and preference for cesarean section - A cross-sectional study at various stages of pregnancy in Sweden. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(7):807-13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340902998436.

- Yildiz PD, Ayers S, Phillips L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:634-45. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.009.

- Sydsjö G, Möller L, Lilliecreutz C, Bladh M, Andolf E, Josefsson A. Psychiatric illness in women requesting caesarean section. BJOG. 2015;122(3):351-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12714.

- Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Zhang J, Gulmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148343. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148343.

- Rayyan QCRI. [Available from: https://rayyan.qcri.org/welcome.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

- Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverkets allmänna råd. TLVAR 2017. Stockholm: Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverket (TLV); 2017. [accessed Oct 26 2021]. Available from: https://www.tlv.se/download/18.467926b615d084471ac3230c/1510316374332/TLVAR_2017_1.pdf.

- Boyle SE, Jones GL, Walters SJ. Physical activity, quality of life, weight status and diet in adolescents. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(7):943-54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9659-8.

- Doring N, de Munter J, Rasmussen F. The associations between overweight, weight change and health related quality of life: Longitudinal data from the Stockholm Public Health Cohort 2002-2010. Prev Med. 2015;75:12-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.007.

- John J, Wolfenstetter SB, Wenig CM. An economic perspective on childhood obesity: recent findings on cost of illness and cost effectiveness of interventions. Nutrition. 2012;28(9):829-39. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2011.11.016.

- Nationella KPP-principer, version 4. Kostnad per Patient. Stockholm: Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner (SKR); 2020. [accessed Oct 26 2021]. Available from: https://webbutik.skr.se/bilder/artiklar/pdf/7585-881-4.pdf.

- Prislista för utomlänsvård samt för EU/EES och Schweiz 2021. Stockholm: Karolinska Universitetssjukhuset och Region Stockholm; 2021. [accessed Dec 18 2021]. Available from: https://www.regionstockholm.se/globalassets/5.-politik/politiska-organ/samverkansnamnden-sthlm-gotland/2021/prislistor-2021/bilaga-2-karolinska-universitetssjukhuset-2021.pdf.

- Geller EJ, Wu JM, Jannelli ML, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. Neonatal outcomes associated with planned vaginal versus planned primary cesarean delivery. J Perinatol. 2010;30(4):258-64. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2009.150.

- Socialstyrelsen. Stockholm. [accessed Dec 17 2021]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/utveckla-verksamhet/e-halsa/klassificering-och-koder/drg/viktlistor/.

- Jansson SA, Rönmark E, Forsberg B, Löfgren C, Lindberg A, Lundbäck B. The economic consequences of asthma among adults in Sweden. Respir Med. 2007;101(11):2263-70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.029.

- Fox M, Mugford M, Voordouw J, Cornelisse-Vermaat J, Antonides G, de la Hoz Caballer B, et al. Health sector costs of self-reported food allergy in Europe: a patient-based cost of illness study. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(5):757-62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt010.

- Khalili H, Everhov AH, Halfvarson J, Ludvigsson JF, Askling J, Myrelid P, et al. Healthcare use, work loss and total costs in incident and prevalent Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: results from a nationwide study in Sweden. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52(4):655-68. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.15889.

- Tiberg I, Lindgren B, Carlsson A, Hallström I. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses of hospital-based home care compared to hospital-based care for children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes; a randomised controlled trial; results after two years' follow-up. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:94. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0632-8.

- Kuhlmann A, Schmidt T, Treskova M, Lopez-Bastida J, Linertova R, Oliva-Moreno J, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Europe. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17 Suppl 1:79-87. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-016-0786-1.

- Arber M, Garcia S, Veale T, Edwards M, Shaw A, Glanville JM. Performance of Ovid Medline Search Filters to Identify Health State Utility Studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;33(4):472-80. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462317000897.

- Jensen CC, Prasad LM, Abcarian H. Cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic vs open resection for colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(10):1017-23. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182656898.

- Manca A, Sculpher MJ, Ward K, Hilton P. A cost-utility analysis of tension-free vaginal tape versus colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence. BJOG. 2003;110(3):255-62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.02215.x.

- Rosen MJ, Bauer JJ, Harmaty M, Carbonell AM, Cobb WS, Matthews B, et al. Multicenter, Prospective, Longitudinal Study of the Recurrence, Surgical Site Infection, and Quality of Life After Contaminated Ventral Hernia Repair Using Biosynthetic Absorbable Mesh: The COBRA Study. Ann Surg. 2017;265(1):205-11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001601.

- van der Wal JB, Iordens GI, Vrijland WW, van Veen RN, Lange J, Jeekel J. Adhesion prevention during laparotomy: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2011;253(6):1118-21. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318217e99c.

- Glazener C, Breeman S, Elders A, Hemming C, Cooper K, Freeman R, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of surgical options for the management of anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall prolapse: two randomised controlled trials within a comprehensive cohort study - results from the PROSPECT Study. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 2016;20(95):1-452.

- Willems DC, Joore MA, Hendriks JJ, Wouters EF, Severens JL. Cost-effectiveness of a nurse-led telemonitoring intervention based on peak expiratory flow measurements in asthmatics: results of a randomised controlled trial. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2007;5:10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-5-10.

- Protudjer JL, Jansson SA, Östblom E, Arnlind MH, Bengtsson U, Dahlen SE, et al. Health-related quality of life in children with objectively diagnosed staple food allergy assessed with a disease-specific questionnaire. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(10):1047-54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13044.

- Huaman JW, Casellas F, Borruel N, Pelaez A, Torrejon A, Castells I, et al. Cutoff values of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire to predict a normal health related quality of life. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(6):637-41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2010.07.006.

- Lee JM, Rhee K, O'Grady M J, Basu A, Winn A, John P, et al. Health utilities for children and adults with type 1 diabetes. Med Care. 2011;49(10):924-31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318216592c.

- Epps H, Ginnelly L, Utley M, Southwood T, Gallivan S, Sculpher M, et al. Is hydrotherapy cost-effective? A randomised controlled trial of combined hydrotherapy programmes compared with physiotherapy land techniques in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(39):iii-iv, ix-x, 1-59. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3310/hta9390.

- Burström K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F. Health-related quality of life by disease and socio-economic group in the general population in Sweden. Health Policy. 2001;55(1):51-69. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00111-1.

- Åstrom M, Persson C, Linden-Boström M, Rolfson O, Burström K. Population health status based on the EQ-5D-Y-3L among adolescents in Sweden: Results by sociodemographic factors and self-reported comorbidity. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(11):2859-71. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1985-2.

- Gilbert SA, Grobman WA, Landon MB, Varner MW, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, et al. Lifetime cost-effectiveness of trial of labor after cesarean in the United States. Value Health. 2013;16(6):953-64. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2013.06.014.

- Statistik om graviditeter, förlossningar och nyfödda. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2019. [accessed Dec 20 2021]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/statistik/statistikamnen/graviditeter-forlossningar-och-nyfodda/.

- SBU. Etiska aspekter på insatser inom hälso- och sjukvården. En vägledning för att identifiera relevanta etiska aspekter. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2021. [accessed Dec 16 2021]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/etiska_aspekter_halso_sjukvarden.pdf.

- Ahlqvist VH, Persson M, Magnusson C, Berglind D. Elective and nonelective cesarean section and obesity among young adult male offspring: A Swedish population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(12). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002996.

- Tun HM, Bridgman SL, Chari R, Field CJ, Guttman DS, Becker AB, et al. Roles of Birth Mode and Infant Gut Microbiota in Intergenerational Transmission of Overweight and Obesity From Mother to Offspring. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018;172(4):368-77. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5535.

- Komplikationer efter förlossning. Riskfaktorer för bristningar, samt direkta och långsiktiga komplikationer. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2018. [accessed 13 dec 2021]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2018-5-20.pdf.

- Andolf E, Thorsell M, Klln K. Cesarean delivery and risk for postoperative adhesions and intestinal obstruction: A nested case-control study of the Swedish Medical Birth Registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):406.e1-.e6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.07.013.

- Larsson C, Källen K, Andolf E. Cesarean section and risk of pelvic organ prolapse: a nested case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(3):243.e1-.e4. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2008.11.028.

- Leijonhufvud A, Lundholm C, Cnattingius S, Granath F, Andolf E, Altman D. Risks of stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse surgery in relation to mode of childbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(1):70.e1-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.034.

- Persson J, Wolner-Hanssen P, Rydhstroem H. Obstetric risk factors for stress urinary incontinence: a population-based study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(3):440-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00950-9.

- Åkervall S, Al-Mukhtar Othman J, Molin M, Gyhagen M. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in middle-aged women: a national matched cohort study on the influence of childbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(4):356.e1-.e14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.007.

- Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, Hunskaar S, Norwegian ES. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(10):900-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa021788.

- Abenhaim HA, Tulandi T, Wilchesky M, Platt R, Spence AR, Czuzoj-Shulman N, et al. Effect of Cesarean Delivery on Long-term Risk of Small Bowel Obstruction. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(2):354-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002440.

- Schwarzman P, Paz Levy D, Walfisch A, Sergienko R, Bernstein EH, Sheiner E. Pelvic floor disorders following different delivery modes—a population-based cohort analysis. International Urogynecology Journal. 2020;31(3):505-11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04151-0.

- Kolås T, Saugstad OD, Daltveit AK, Nilsen ST, Oian P. Planned cesarean versus planned vaginal delivery at term: comparison of newborn infant outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(6):1538-43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.005.

- Hansen AK, Wisborg K, Uldbjerg N, Henriksen TB. Risk of respiratory morbidity in term infants delivered by elective caesarean section: cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7635):85-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39405.539282.BE.

- Norman M, Aberg K, Holmsten K, Weibel V, Ekeus C. Predicting Nonhemolytic Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):1087-94. Available from: https://doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2001.

- Carlsson Wallin M, Ekström P, Marsal K, Källén K. Apgar score and perinatal death after one previous caesarean delivery. BJOG. 2010;117(9):1088-97. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02614.x.

- Wood S, Ross S, Sauve R. Cesarean section and subsequent stillbirth, is confounding by indication responsible for the apparent association? An updated cohort analysis of a large perinatal database. PLoS One. 2015;10(9).

- Lassey SC, Robinson JN, Kaimal AJ, Little SE. Outcomes of Spontaneous Labor in Women Undergoing Trial of Labor after Cesarean as Compared with Nulliparous Women: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(9):852-7.

- Macharey G, Toijonen A, Hinnenberg P, Gissler M, Heinonen S, Ziller V. Term cesarean breech delivery in the first pregnancy is associated with an increased risk for maternal and neonatal morbidity in the subsequent delivery: a national cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;302(1):85-91. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05575-6.

- Visser L, Slaager C, Kazemier BM, Rietveld AL, Oudijk MA, de Groot C, et al. Risk of preterm birth after prior term cesarean. BJOG. 2020;127(5):610-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16083.

- Williams C, Fong R, Murray SM, Stock SJ. Caesarean birth and risk of subsequent preterm birth: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128(6):1020-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16566.

- Almqvist C, Cnattingius S, Lichtenstein P, Lundholm C. The impact of birth mode of delivery on childhood asthma and allergic diseases--a sibling study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(9):1369-76. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04021.x.

- Bråback L, Ekeus C, Lowe AJ, Hjern A. Confounding with familial determinants affects the association between mode of delivery and childhood asthma medication - a national cohort study. Allergy, Asthma, & Clinical Immunology : Official Journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2013;9(1):14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1710-1492-9-14.

- Håkansson S, Källén K. Caesarean section increases the risk of hospital care in childhood for asthma and gastroenteritis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(6):757-64. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01667.x.

- Khashan AS, Kenny LC, Lundholm C, Kearney PM, Gong T, Almqvist C. Mode of obstetrical delivery and type 1 diabetes: A sibling design study. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):e806-e13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0819.

- Malmborg P, Bahmanyar S, Grahnquist L, Hildebrand H, Montgomery S. Cesarean section and the risk of pediatric crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(4):703-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21741.

- Mitselou N, Hallberg J, Stephansson O, Almqvist C, Melén E, Ludvigsson JF. Cesarean delivery, preterm birth, and risk of food allergy: Nationwide Swedish cohort study of more than 1 million children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(5):1510-4.e2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.06.044.

- Mitselou N, Hallberg J, Stephansson O, Almqvist C, Melén E, Ludvigsson JF. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and risk of later allergic rhinitis—Nationwide Swedish cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31(5):471-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.13230.

- Andersen V, Möller S, Jensen PB, Møller FT, Green A. Caesarean delivery and risk of chronic inflammatory diseases (Inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, coeliac disease, and diabetes mellitus): A population based registry study of 2,699,479 births in Denmark during 1973–2016. Clin Epidemiol. 2020;12:287-93. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S229056.

- Clausen TD, Bergholt T, Eriksson F, Rasmussen S, Keiding N, Løkkegaard EC. Prelabor cesarean section and risk of childhood type 1 diabetes: A nationwide register-based cohort study. Epidemiology. 2016;27(4):547-55. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000488.

- Dydensborg Sander S, Hansen AV, Stordal K, Andersen AN, Murray JA, Husby S. Mode of delivery is not associated with celiac disease. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:323-32. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S152168.

- Kristensen K, Henriksen L. Cesarean section and disease associated with immune function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(2):587-90. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.040.

- Momen NC, Olsen J, Gissler M, Cnattingius S, Li J. Delivery by caesarean section and childhood cancer: A nationwide follow-up study in three countries. BJOG. 2014;121(11):1343-50. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12667.

- Sevelsted A, Stokholm J, Bisgaard H. Risk of Asthma from Cesarean Delivery Depends on Membrane Rupture. J Pediatr. 2016;171:38-42e4. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.066.

- Alterman N, Kurinczuk JJ, Quigley MA. Caesarean section and severe upper and lower respiratory tract infections during infancy: Evidence from two UK cohorts. PLoS One. 2021;16(2 February). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246832.

- Blustein J, Attina T, Liu M, Ryan AM, Cox LM, Blaser MJ, et al. Association of caesarean delivery with child adiposity from age 6 weeks to 15 years. Int J Obes. 2013;37(7):900-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.49.

- Hanrahan M, McCarthy FP, O'Keeffe GW, Khashan AS. The association between caesarean section and cognitive ability in childhood. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(9):1231-40. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01798-4.

- Richards M, Ferber J, Chen H, Swor E, Quesenberry CP, Li DK, et al. Caesarean delivery and the risk of atopic dermatitis in children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50(7):805-14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.13668.

- Richards M, Ferber J, Li DK, Darrow LA. Cesarean delivery and the risk of allergic rhinitis in children. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2020;125(3):280-6.e5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2020.04.028.

- Sitarik AR, Havstad SL, Johnson CC, Jones K, Levin AM, Lynch SV, et al. Association between cesarean delivery types and obesity in preadolescence. Int J Obes. 2020;44(10):2023-34. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-00663-8.

- Begum M, Pilkington R, Chittleborough C, Lynch J, Penno M, Smithers L. Caesarean section and risk of type 1 diabetes: whole-of-population study. Diabet Med. 2019;36(12):1686-93. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14131.

- Moore HC, de Klerk N, Holt P, Richmond PC, Lehmann D. Hospitalisation for bronchiolitis in infants is more common after elective caesarean delivery. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(5):410-4. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2011-300607.

- Keski-Nisula L, Karvonen A, Pfefferle PI, Renz H, Büchele G, Pekkanen J. Birth-related factors and doctor-diagnosed wheezing and allergic sensitization in early childhood. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010;65(9):1116-25. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02322.x.

- Korhonen P, Haataja P, Ojala R, Hirvonen M, Korppi M, Paassilta M, et al. Asthma and atopic dermatitis after early-, late-, and post-term birth. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53(3):269-77. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.23942.

- Li H, Ye R, Pei L, Ren A, Zheng X, Liu J. Caesarean delivery, caesarean delivery on maternal request and childhood overweight: A Chinese birth cohort study of 181380 children. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9(1):10-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00151.x.

- Li HT, Ye RW, Pei LJ, Ren AG, Zheng XY, Liu JM. Cesarean delivery on maternal request and childhood intelligence: A cohort study. Chin Med J. 2011;124(23):3982-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2011.23.025.

- Masukume G, Khashan AS, Morton SMB, Baker PN, Kenny LC, McCarthy FP. Caesarean section delivery and childhood obesity in a British longitudinal cohort study. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2019;14(10):e0223856. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223856.

- Masukume G, McCarthy FP, Baker PN, Kenny LC, Morton SM, Murray DM, et al. Association between caesarean section delivery and obesity in childhood: a longitudinal cohort study in Ireland. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e025051. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025051.

- Masukume G, McCarthy FP, Russell J, Baker PN, Kenny LC, Morton SM, et al. Caesarean section delivery and childhood obesity: evidence from the growing up in New Zealand cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019;73(12):1063-70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-212591.

- Tollånes MC, Moster D, Daltveit AK, Irgens LM. Cesarean Section and Risk of Severe Childhood Asthma: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J Pediatr. 2008;153(1):112-6.e1. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.01.029.

- Mitselou N, Hallberg J, Stephansson O, Almqvist C, Melen E, Ludvigsson JF. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and risk of later allergic rhinitis-Nationwide Swedish cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31:471-79. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.13230.

- Kennedy HP, Grant J, Walton C, Sandall J. Elective caesarean delivery: a mixed method qualitative investigation. Midwifery. 2013;29(12):e138-44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.12.008.

- Panda S, Daly D, Begley C, Karlström A, Larsson B, Back L, et al. Factors influencing decision-making for caesarean section in Sweden - a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):377. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2007-7.

- Eide KT, Bærøe K. How to reach trustworthy decisions for caesarean sections on maternal request: A call for beneficial power. J Med Ethics. 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106071.

- Eide KT, Morken NH, Baeroe K. Maternal reasons for requesting planned cesarean section in Norway: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):102. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2250-6.

- Emmett CL, Shaw AR, Montgomery AA, Murphy DJ, Di Asg. Women's experience of decision making about mode of delivery after a previous caesarean section: the role of health professionals and information about health risks. BJOG. 2006;113(12):1438-45. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01112.x.

- Fenwick J, Gamble J, Hauck Y. Reframing birth: a consequence of cesarean section. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(2):121-30; discussion 31-2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03991_1.x.

- Fenwick J, Staff L, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Bayes S. Why do women request caesarean section in a normal, healthy first pregnancy? Midwifery. 2010;26(4):394-400. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2008.10.011.

- Karlström A, Engström-Olofsson R, Nystedt A, Thomas J, Hildingsson I. Swedish caregivers' attitudes towards caesarean section on maternal request. Women & Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives. 2009;22(2):57-63. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2008.12.002.

- Kenyon SL, Johns N, Duggal S, Hewston R, Gale N. Improving the care pathway for women who request Caesarean section: an experience-based co-design study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):348. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1134-2.

- McGrath P, Phillips E, Ray-Barruel G. Bioethics and birth: insights on risk decision-making for an elective caesarean after a prior caesarean delivery. Monash Bioeth Rev. 2009;28(3):22.1-19.

- Ramvi E, Tangerud M. Experiences of women who have a vaginal birth after requesting a cesarean section due to a fear of birth: a biographical, narrative, interpretative study. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13(3):269-74. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00614.x.

- Sahlin M, Carlander-Klint AK, Hildingsson I, Wiklund I. First-time mothers' wish for a planned caesarean section: deeply rooted emotions. Midwifery. 2013;29(5):447-52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.02.009.

- Weaver JJ, Statham H, Richards M. Are there "unnecessary" cesarean sections? Perceptions of women and obstetricians about cesarean sections for nonclinical indications. Birth. 2007;34(1):32-41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00144.x.

- Kornelsen J, Hutton E, Munro S. Influences on decision making among primiparous women choosing elective caesarean section in the absence of medical indications: findings from a qualitative investigation. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology Canada: JOGC. 2010;32(10):962-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34684-9.

- Kamal P, Dixon-Woods M, Kurinczuk JJ, Oppenheimer C, Squire P, Waugh J. Factors influencing repeat caesarean section: qualitative exploratory study of obstetricians' and midwives' accounts. BJOG. 2005;112(8):1054-60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00647.x.

- Allen VM, O'Connell CM, Baskett TF. Cumulative economic implications of initial method of delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Pt 1):549-55. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000228511.42529.a5.

- Allen VM, O'Connell CM, Farrell SA, Baskett TF. Economic implications of method of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):192-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.635.

- Caesarean section (NICE clinical guideline 132). London: The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2011. [accessed Oct 26 2021]. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/caesarean-section-nice-clinical-guideline-132/.

- Xu X, Ivy JS, Patel DA, Patel SN, Smith DG, Ransom SB, et al. Pelvic floor consequences of cesarean delivery on maternal request in women with a single birth: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Womens Health. 2010;19(1):147-60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2009.1404.

- Fawsitt CG, Bourke J, Greene RA, Everard CM, Murphy A, Lutomski JE. At what price? A cost-effectiveness analysis comparing trial of labour after previous caesarean versus elective repeat caesarean delivery. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2013;8(3):e58577. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058577.

- Fobelets M, Beeckman K, Faron G, Daly D, Begley C, Putman K. Vaginal birth after caesarean versus elective repeat caesarean delivery after one previous caesarean section: a cost-effectiveness analysis in four European countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):92. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1720-6.

- Arbets- och Referensgruppen för Hemostasrubbningar. Hemostasrubbningar inom obstetrik och gynekologi: SFOG; 2018 Rapport nr: 79. [accessed Dec 17 2021]. Available from: https://www.sfog.se/natupplaga/SFOG_nr79cdcc5acb-e759-4fab-834d-7953f6204054.pdf.

- SBU. Förlossningsbristningar – Diagnostik samt erfarenheter av bemötande och information. ISBN 978-91-88437-67-9. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2021 323. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/323.

- SBU. Analsfinkterskador vid förlossning. ISBN 978-91-85413-92-8. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2016 249. Available from: www.sbu.se/249.

- Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, Mola G, Visser GH, Homer CS, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1349-57. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31930-5.

- Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ, Rouse DJ, et al. Development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):806-12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000259312.36053.02.

- Dy J, DeMeester S, Lipworth H, Barrett J. No. 382-Trial of Labour After Caesarean. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology Canada: JOGC. 2019;41(7):992-1011. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2018.11.008.

- Halvorsen L, Nerum H, Sorlie T, Oian P. Does counsellor's attitude influence change in a request for a caesarean in women with fear of birth? Midwifery. 2010;26(1):45-52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2008.04.011.

- Nerum H, Halvorsen L, Sorlie T, Oian P. Maternal request for cesarean section due to fear of birth: can it be changed through crisis-oriented counseling? Birth. 2006;33(3):221-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00107.x.

- Giddens A, Sutton P. Sociologi. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2014.

- Hildingsson I. How much influence do women in Sweden have on caesarean section? A follow-up study of women's preferences in early pregnancy. Midwifery. 2008;24(1):46-54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2006.07.007.

- Habiba M, Kaminski M, Da Fre M, Marsal K, Bleker O, Librero J, et al. Caesarean section on request: a comparison of obstetricians' attitudes in eight European countries. BJOG. 2006;113(6):647-56. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00933.x.

- Bt Maznin NL, Creedy DK. A comprehensive systematic review of factors influencing women's birthing preferences. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10(4):232-306. Available from: https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2012-46.

- O'Donovan C, O'Donovan J. Why do women request an elective cesarean delivery for non-medical reasons? A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Birth. 2018;45(2):109-19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12319.

- Svenska Barnmorskeförbundet. Policydokument. Vårdformer. Stockholm; 2019. Available from: https://storage.googleapis.com/barnmorskeforbundet-se/uploads/2020/01/Policydokument-Vardformer-2019-Svenska-Barnmorskeforbundet.pdf.

- Kingdon C, Downe S, Betran AP. Non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean section targeted at organisations, facilities and systems: Systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0203274. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203274.

- Stärk förlossningsvården och kvinnors hälsa. Slutredovisning av regeringsuppdrag om förlossningsvården och hälso- och sjukvård som rör kvinnors hälsa.: Socialstyrelsen; 2019. [accessed Oct 1 2021]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2019-12-6531.pdf.

- Loke AY, Davies L, Mak YW. Is it the decision of women to choose a cesarean section as the mode of birth? A review of literature on the views of stakeholders. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):286. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2440-2.

- Horey D, Kealy M, Davey MA, Small R, Crowther CA. Interventions for supporting pregnant women's decision-making about mode of birth after a caesarean. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(7):CD010041. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010041.pub2.

- Halfdansdottir B, Wilson ME, Hildingsson I, Olafsdottir OA, Smarason AK, Sveinsdottir H. Autonomy in place of birth: a concept analysis. Med Health Care Philos. 2015;18(4):591-600. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-015-9624-y.

- Beauchamp TL, Walters L. Ethical theory and bioethics. In: Contemporary issues in bioethics, 6th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth; 2003. p. 1-37.

- Keedle H, Schmied V, Burns E, Dahlen HG. The journey from pain to power: A meta-ethnography on women's experiences of vaginal birth after caesarean. Women & Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives. 2018;31(1):69-79. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.008.

- Kennedy K, Adelson P, Fleet J, Steen M, McKellar L, Eckert M, et al. Shared decision aids in pregnancy care: A scoping review. Midwifery. 2020;81:102589. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.102589.

- Coxon K, Homer C, Bisits A, Sandall J, Bick DE. Reconceptualising risk in childbirth. Midwifery. 2016;38:1-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.05.012.

- Symon A, Winter C, Donnan PT, Kirkham M. Examining Autonomy's Boundaries: A Follow-up Review of Perinatal Mortality Cases in UK Independent Midwifery. Birth. 2010;37(4):280-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00422.x.

- Home birth--proceed with caution. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):303. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61165-8.

- Olieman RM, Siemonsma F, Bartens MA, Garthus-Niegel S, Scheele F, Honig A. The effect of an elective cesarean section on maternal request on peripartum anxiety and depression in women with childbirth fear: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):195. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1371-z.

- Garthus-Niegel S, von Soest T, Knoph C, Simonsen TB, Torgersen L, Eberhard-Gran M. The influence of women's preferences and actual mode of delivery on post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth: a population-based, longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:191. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-191.

- Sobocki P, Ekman M, Agren H, Krakau I, Runeson B, Mårtensson B, et al. Resource use and costs associated with patients treated for depression in primary care. Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8(1):67-76. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-006-0008-3.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375-83. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02840-3.

- NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request. NIH Consens Sci Statements. 2006:1-29.

- Gilbert SA, Grobman WA, Landon MB, Spong CY, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of trial of labor after previous cesarean in a minimally biased cohort. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30(1):11-20. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1333206.

- Larsson B, Karlström A, Rubertsson C, Ternström E, Ekdahl J, Segebladh B, et al. Birth preference in women undergoing treatment for childbirth fear: A randomised controlled trial. Women Birth. 2017;30(6):460-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.04.004.

- Hildingsson I, Karlström A, Rubertsson C, Haines H. Women with fear of childbirth might benefit from having a known midwife during labour. Women & Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives. 2019;32(1):58-63. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.04.014.

- Hildingsson I, Rubertsson C, Karlström A, Haines H. Caseload midwifery for women with fear of birth is a feasible option. Sexual & reproductive healthcare : official journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives. 2018;16:50-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2018.02.006.

- Hildingsson I, Rubertsson C, Karlström A, Haines H. A known midwife can make a difference for women with fear of childbirth- birth outcome and women's experiences of intrapartum care. Sexual & reproductive healthcare : official journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives. 2019;21:33-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2019.06.004.

- Larsson B, Rubertsson C, Hildingsson I. A modified caseload midwifery model for women with fear of birth, women's and midwives' experiences: A qualitative study. Sexual & reproductive healthcare : official journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives. 2020;24:100504. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2020.100504.

- Lyberg A, Severinsson E. Fear of childbirth: mothers' experiences of team-midwifery care -- a follow-up study. Journal of Nursing Management (John Wiley & Sons, Inc). 2010;18(4):383-90. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01103.x.

- Striebich S, Ayerle GM. Fear of childbirth (FOC): pregnant women's perceptions towards the impending hospital birth and coping resources - a reconstructive study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;41(3):231-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2019.1657822.

- Sydsjö G, Blomberg M, Palmquist S, Angerbjörn L, Bladh M, Josefsson A. Effects of continuous midwifery labour support for women with severe fear of childbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:115. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0548-6

- Rogers AJ, Rogers NG, Kilgore ML, Subramaniam A, Harper LM. Economic Evaluations Comparing a Trial of Labor with an Elective Repeat Cesarean Delivery: A Systematic Review. Value Health. 2017;20(1):163-73. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.08.738.

- Kejsarsnitt. Rapport nr 65. Stockholm: Svensk Förening för Obstetrik och Gynekologi (SFOG); 2010. [accessed Oct 26 2021]. Available from: https://www.sfog.se/natupplaga/ARG6546953362-8e9e-4acd-bd5b-ff9f6415419d.pdf.

Scientific articles

Johansson M, Alvan J, Pettersson A, Hildingsson I. Conflicting attitudes between clinicians and women regarding maternal requested caesarean section: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2023;23(1):210. Open access

Berg J, Källén K, Andolf E, Hellström-Westas L, Ekéus C, Alvan J, et al. Economic Evaluation of Elective Cesarean Section on Maternal Request Compared With Planned Vaginal Birth—Application to Swedish Setting Using National Registry Data. Value in Health. 2022.Open access

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Share via Email