Psychological Treatment for Postpartum Depression

A systematic review including health economic and ethical aspects

Conclusions

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) provides a medium-sized1 decrease in depression symptoms both immediately after the treatment and up to six months after treatment, compared to usual care (moderate certainty of evidence).

- Interpersonal therapy (IPT) provides a large decrease in depression symptoms immediately after the treatment, compared to usual care (low certainty of evidence).

- Supportive counselling provides a decrease in depression symptoms up to six months after the treatment, compared to usual care (low certainty of evidence).

1. In the report's conclusions on treatment effects, Cohen's d is used as the size of the treatment effect. Effects of 0.20–0.50 are assessed as small, 0.50–0.80 as medium and effects greater than 0.80 as large. The certainty of the conclusions is assessed with GRADE. It is the magnitude of the effects that is assessed with GRADE.

Background

A depression episode that occurs in a parent within the first few months after the baby has been born is defined as a postpartum depression (PPD). Common symptoms of PPD include depression, difficulty sleeping, anxiety and feelings of guilt. About 13% of women suffer from some degree of depression symptoms in the first months after childbirth, which is slightly higher than during other periods of life.

In healthcare various types of interventions are offered, mainly psychological and pharmacological treatments2. In the Swedish model for PPD care, the intervention is often given in the form of person-centered supportive counselling as a first step3, with the opportunity to refer further if necessary for in-depth assessment and other treatments such as psychotherapy. This can be given based on different treatment models such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy (IPT), and in different formats such as group therapy or individually, given at the clinic or via the internet. In the National Board of Health and Welfare's treatment guidelines, CBT and IPT are primarily recommended as psychological treatments for mild to moderate depression. Research shows that women with PPD prefer psychological treatment and psychosocial interventions to, for example, pharmacological treatment.

2. An overview of the overview of the state of research on antidepressant treatment for PPD was published as a SBU Comments.

3. Women are first screened using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and accompanying interview.

Aim

The purpose of this report was to evaluate the scientific support for professionally given psychological treatments and psychosocial interventions given to women with PPD, and to investigate what lived experiences women have of such treatments and interventions. The report also includes an analysis of health economic aspects and an ethical discussion of the review's results.

The methodology and findings of the qualitative meta-synthesis will be published separately in a scientific journal.

Method

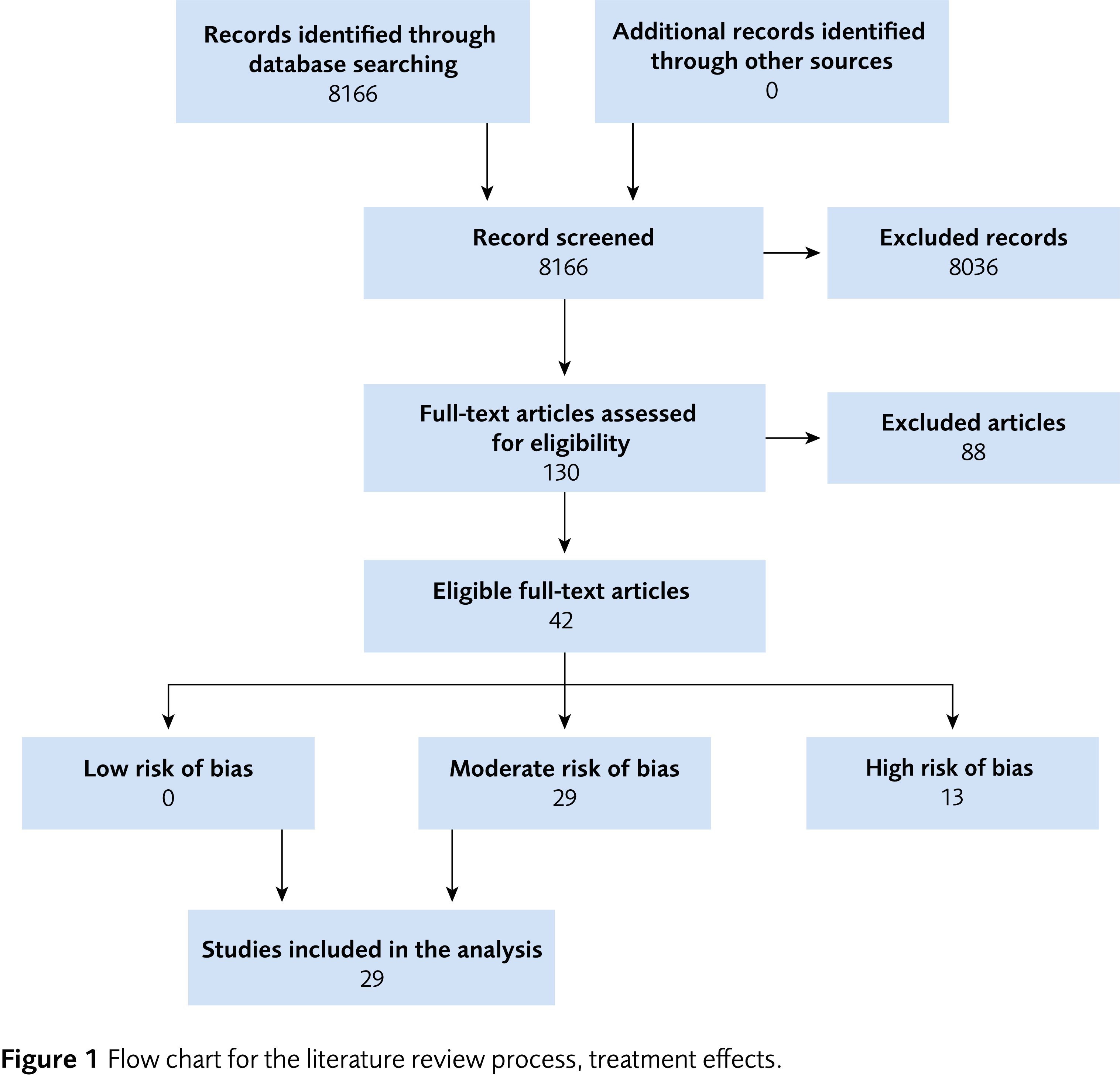

We conducted a systematic review and reported it in accordance with the PRISMA statement. The protocol is registered in Prospero (CRD42022313215). The certainty of evidence was assessed with GRADE.

Inclusion criteria

Population

Women (adults) with depression during postpartum period (up to 12 months after birth). Depression must be diagnosed with a clinical interview or exceed the clinical threshold on a validated depression instrument.

Intervention

Any psychological or psychosocial intervention given in primary health care to treat depressive symptoms.

Control

Treatment as usual or other active treatment, waiting list or no treatment. Pharmacological treatments were excluded.

Outcome

Degree of depression symptoms measured with validated depression instruments. For health economic analyses, we also included the outcomes health related quality of life (as measured with EQ-5D or SF-6D).

Study design

Prospective clinical trials with a control group, with or without randomisation.

Language

English, Norwegian, Danish or Swedish.

Search period

From 1995 to 2022. Final search August 2022.

Databases searched

CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO and Scopus.

Patient involvement

No.

Results

We included 29 studies concerning the effects of depression treatments, conducted in eleven countries, and two studies on health economic aspects.

Most of the studies included in the assessment examined the effects of CBT (15 studies). Other forms of treatment included are IPT (6 studies), supportive counselling (4 studies), interventions to promote parental responsiveness and child development (3 studies) and a specific form of group therapy with elements of, among other things, CBT (1 study). The comparisons were mainly against usual care. The study populations in the efficacy studies consisted of women with varying degrees of depression symptoms. No adverse effects were reported in the included studies. The table presents summarized results for each intervention.

| CBT = Cognitive behavioural therapy; CI = Confidence interval; IPT = Interpersonal therapy; NNT = Number needed to treat, which has been converted from the mean difference, and indicates the number of individuals who need to be treated to observe a favorable treatment outcome with decrease in depression symptoms. The lower the NNT, the stronger the treatment effect. * The treatment was a group therapy with elements of psychoeducation, stress-reducing techniques, cognitive restructuring, and social support. ** NNT was not calculated for non-significant results. |

||||

| Treatment | Time of outcome measurement | Results Cohen’s d (95% CI) and NNT |

GRADE | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | After the treatment 3–6 months |

−0.59 (−0.69 to −0.49) and 4.7 −0.58 (−0.75 to −0.41) and 4.8 |

⊕⊕⊕◯ | CBT is likely to have a medium-sized effect on decreasing depression symptoms, both after end of treatment and at follow-up |

| IPT | After the treatment | −0.81 (−1.31 to −0.31) and 3.4 | ⊕⊕◯◯ | IPT may have a major effect on decreasing depression symptoms after end of treatment |

| Supportive counselling | After the treatment 1 week 6 months |

−1.37 (−2.31 to −0.43) and 2.0 −0.89 (−2.07 to 0.30) and ** −0.27 (−0.50 to −0.04) and 11.2 |

⊕⊕◯◯ | Supportive counselling may have an effect on decreasing depression symptoms after end of treatment and after 6 months |

| Parent/ infant treatment |

After the treatment | −0.11 (−0.71 to 0.50) and ** −0.55 (−1.10 to −0.09) and 5.1 |

⊕◯◯◯ | It is unclear what effect the interventions have |

| Other form of therapy* | After the treatment | −1.07 (−2.20 to 0.06) and ** | ⊕◯◯◯ | It is unclear what effect the intervention has |

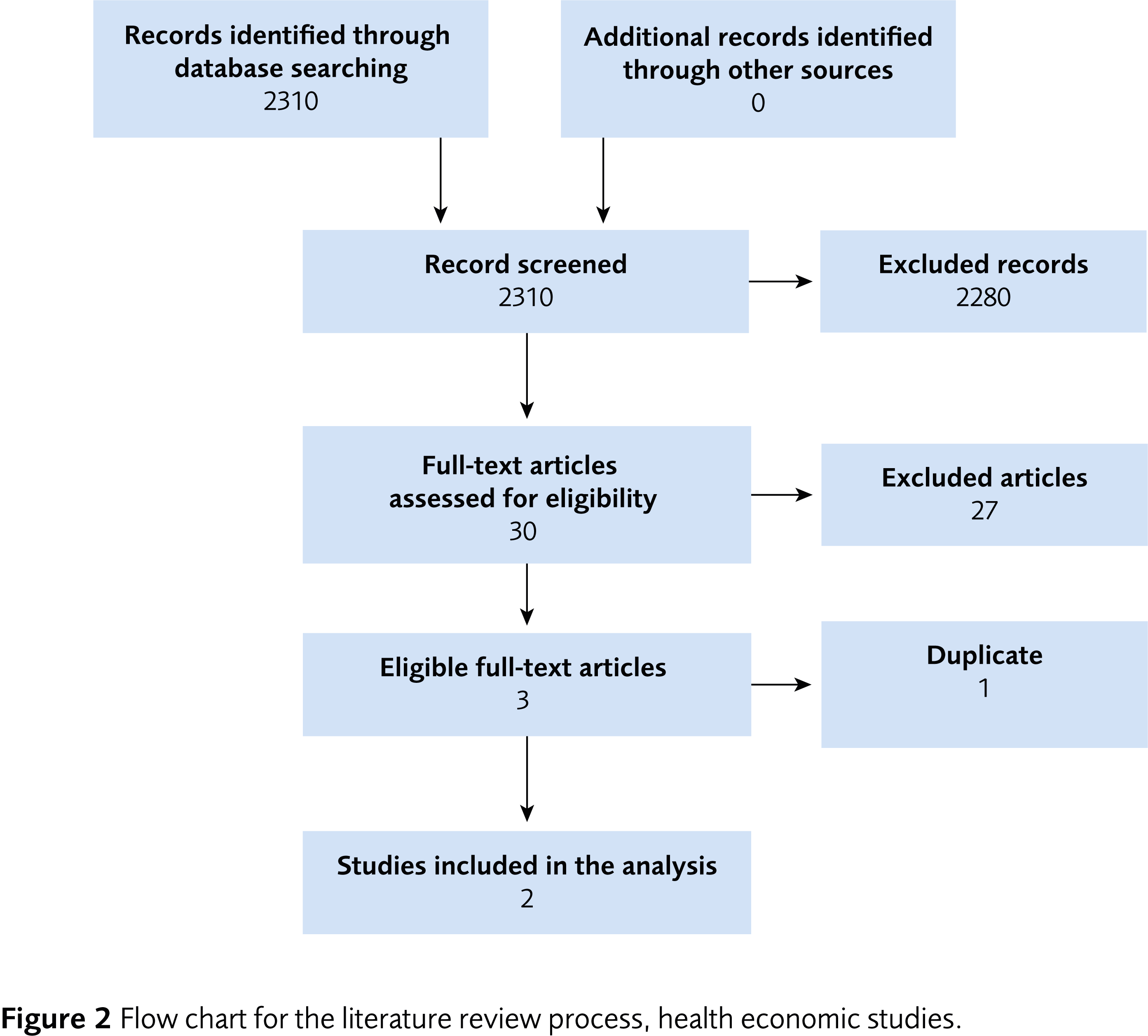

Health Economic Assessment

The cost-effectiveness of psychological treatments and supportive counselling in postpartum depression has not been assessed due to few health economic evaluations for the treatment of PPD. Only two studies, both form the United Kingdom, were included in the health economic assessment. Although the different treatment formats differ regarding costs, individual needs of the women and the organisation of healthcare must be considered.

Ethics

In brief, it is important that women with PPD receives care in line with individual needs. The ethical value of autonomy was discussed, where one finding was that women wanted to be able to choose the treatment model and format. One possible ethical problem discussed in the report is that access to care interventions is not equal across the country, and that women with a migration background risk having poorer access to care.

Discussion

The report provides support for both CBT and IPT as treatment options for postpartum depression, compared to treatment as usual. The report does not compare treatments with each other but evaluates their effects separately. For CBT, we found a medium-sized average effect, based on several studies. For IPT, a large effect was observed, based on a smaller number of studies. A smaller number of studies and fewer participants means that the estimated effect size is more uncertain. For IPT, unlike CBT, there were no basis for assessing the effects of treatment on follow-up measurements (3–6 months after treatment).

Our report also provides some support for a decrease in depression symptoms with supportive counselling, but the data did not allow for a formal meta-analysis. Our report provides support that the interventions within the Swedish care model for mild to moderate depression postpartum have an effect and are appreciated by the treated women. No adverse effects of the treatments have emerged in the included studies.

We found no controlled studies with low risk of bias that, besides effects on a woman's depression symptoms, have investigated effects on the parent-child relationship. Furthermore, studies on the effects of psychodynamic therapy (PDT) would be valuable. In addition, studies are generally needed in this field of research that include analyses of what constitute clinically significant changes in depression symptoms at the individual level.

Conflicts of Interest

In accordance with SBU’s requirements, the experts and scientific reviewers participating in this project have submitted statements about conflicts of interest. These documents are available at SBU’s secretariat. SBU has determined that the conditions described in the submissions are compatible with SBU’s requirements for objectivity and impartiality.

The full report in Swedish

The full report in Swedish, Psykologisk behandling av postpartumdepression

Scientific article

Massoudi P, Strömwall LA, Åhlen J, Kärrman Fredriksson M, Dencker A, Andersson E. Women’s experiences of psychological treatment and psychosocial interventions for postpartum depression: a qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Women's Health. 2023;23(1):604. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02772-8

Project group

Experts

- Ewa Andersson, Docent, Associate Professor, Karolinska Institutet

- Anna Dencker, Associate Professor, Senior Lecturer, Institute of Health and Care Sciences, University of Gothenburg

- Pamela Massoudi, PhD, Lic. Clinical Psychologist and Clinical Senior Lecturer, Dept. of Research and Development, Region Kronoberg

- Johan Åhlén, PhD, Project Coordinator, Karolinska Institutet

SBU

- Leif Strömwall, Project Manager

- Naama Kenan Modén, Assistant Project Manager

- Jenny Berg, Health Economist

- Sara Fundell, Project Administrator

- Maja Kärrman Fredriksson, Information Specialist

External reviewers

- Elin Alfredsson, PhD, Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg

- Lisa Ekselius, Senior Professor in Psychiatry, Department of Women´s and Children Health, Uppsala University

- Malin Skoog, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Health Care Strategist, Region Skåne

Flow charts

References

- SBU. Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården och insatser i socialtjänsten: en metodbok. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. [accessed Aug 12 2022]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/metodbok.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181.

- SBU. Antidepressiva läkemedel som behandling vid depression efter förlossningen (postpartumdepression). Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2022. SBU Kommenterar 2022_08. [accessed Aug 30 2022]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/2022_08.

- Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis CL, Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1775-88. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9.

- Howard LM, Khalifeh H. Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):313-27. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20769.

- Putnam KT, Wilcox M, Robertson-Blackmore E, Sharkey K, Bergink V, Munk-Olsen T, et al. Clinical phenotypes of perinatal depression and time of symptom onset: analysis of data from an international consortium. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(6):477-85. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30136-0.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. 5 ed. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders : diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 1993.

- Lydsdottir LB, Howard LM, Olafsdottir H, Thome M, Tyrfingsson P, Sigurdsson JF. The mental health characteristics of pregnant women with depressive symptoms identified by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(4):393-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08646.

- Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, Rizzo DM, Zoretich RA, Hughes CL, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):490-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87.

- Lyubenova A, Neupane D, Levis B, Wu Y, Sun Y, He C, et al. Depression prevalence based on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale compared to Structured Clinical Interview for DSM DIsorders classification: Systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2021;30(1):e1860. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1860.

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1071-83. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db.

- Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, Whiteford HA, Harris MG. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:86-92. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003.

- Massoudi P, Hwang CP, Wickberg B. Fathers' depressive symptoms in the postnatal period: Prevalence and correlates in a population-based Swedish study. Scand J Public Health. 2016;44(7):688-94. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816661652.

- Rubertsson C, Wickberg B, Gustavsson P, Radestad I. Depressive symptoms in early pregnancy, two months and one year postpartum-prevalence and psychosocial risk factors in a national Swedish sample. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):97-104. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-005-0078-8.

- Wickberg B, Hwang CP. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation on a Swedish community sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94(3):181-4. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09845.x.

- Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R, Vigod S, Dennis CL. Prevalence of postpartum depression among immigrant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:67-82. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.08.010.

- Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, Cooper P, Craske MG, Stein A. Association of Persistent and Severe Postnatal Depression With Child Outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):247-53. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4363.

- Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1800-19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0.

- Orth U, Berking M, Burkhardt S. Self-conscious emotions and depression: rumination explains why shame but not guilt is maladaptive. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2006;32(12):1608-19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206292958.

- Brydsten A, Rostila M, Dunlavy A. Social integration and mental health - a decomposition approach to mental health inequalities between the foreign-born and native-born in Sweden. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):48. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0950-1.

- Fair F, Raben L, Watson H, Vivilaki V, van den Muijsenbergh M, Soltani H, et al. Migrant women’s experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and maternity care in European countries: A systematic review. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(2):e0228378. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228378.

- Statistikmyndigheten (SCB). Utrikes födda i Sverige. Statistikmyndigheten. [updated Apr 08 2022; accessed Dec 12 2022]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/utrikes-fodda/.

- Bauer A, Knapp M, Parsonage M. Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:83-90. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.005.

- Cox JL, Holden J, Henshaw C. Perinatal mental health : the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). 2 ed. London: RCPsych Publications; 2014.

- Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer för vård vid depression och ångestsyndrom. Stöd för styrning och ledning. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2021. Artikelnummer 2021-4-7339 [accessed Aug 11 2022]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/nationella-riktlinjer/2021-4-7339.pdf.

- Rikshandboken Barnhälsovård. Screening med EPDS för depression hos nyblivna mammor. Riktlinjer och praktiska anvisningar för screening med EPDS för depression hos nyblivna mammor. Stockholm: Inera AB. [updated May 29 2020; accessed Aug 11 2022]. Available from: https://www.rikshandboken-bhv.se/metoder--riktlinjer/screening-med-epds/.

- SFOG. Mödrahälsovård, Sexuell och reproduktiv Hälsa. Svensk Förening för Obstetrik och Gynekologi (SFOG); 2016. Rapport nr 76. [accessed Aug 11 2022]. Available from: https://www.sfog.se/natupplaga/ARG76web4a328b70-0d76-474e-840e-31f70a89eae9.pdf.

- Kunskapscentrum kvinnohälsa och Kunskapscentrum barnhälsovård. För jämlik mödra- och barnhälsovård i Skåne. En nulägesrapport och underlag för handling. Malmö: Region Skåne; 2019. [accessed Oct 25 2022]. Available from: https://vardgivare.skane.se/contentassets/ce37827f5cc74da8816f1d752ad7ae0f/for-jamlik-modra--och-barnhalsovard-i-skane-2019.pdf.

- Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323-31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00130.x.

- Stewart DE, Vigod S. Postpartum Depression. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2177-86. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1607649.

- Holden JM, Sagovsky R, Cox JL. Counselling in a general practice setting: controlled study of health visitor intervention in treatment of postnatal depression. BMJ. 1989;298(6668):223-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.298.6668.223.

- McCabe JE, Wickberg B, Deberg J, Davila RC, Segre LS. Listening Visits for maternal depression: a meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021;24(4):595-603. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01101-4.

- Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer för vård vid depression och ångestsyndrom. Stöd för styrning och ledning. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2010. Artikelnummer 2010-3-4. [accessed Aug 30 2022]. Available from: https://slf.se/sfbup/app/uploads/2022/03/Riktilinje-SoS-depr-2010-3-4.pdf.

- Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E. The effects of psychological treatment of perinatal depression: an overview. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021;24(5):801-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-021-01159-8.

- Leahy RL. Cognitive Therapy: Basic Principles and Applications. 1 st ed. New Jersey: Jason Aronson, Inc.; 1996.

- Dimidjian S, Martell CR, Herman-Dunn R, Hubley S. Behavioral activation for depression. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (pp 353–393) 5th ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2014.

- Van Lieshout RJ, Layton H, Savoy CD, Brown JSL, Ferro MA, Streiner DL, et al. Effect of Online 1-Day Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Based Workshops Plus Usual Care vs Usual Care Alone for Postpartum Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(11):1200-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2488.

- Wozney L, Olthuis J, Lingley-Pottie P, McGrath PJ, Chaplin W, Elgar F, et al. Strongest Families Managing Our Mood (MOM): a randomized controlled trial of a distance intervention for women with postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(4):525-37. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0732-y.

- Bright KS, Charrois EM, Mughal MK, Wajid A, McNeil D, Stuart S, et al. Interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):248. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1158-6.

- Stuart S. Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19(2):134-40. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1778.

- Stuart S, Robertson MD. Interpersonal psychotherapy : a clinician's guide. 2 ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2012.

- Nylen KJ, Moran TE, Franklin CL, O'Hara M W. Maternal depression: A review of relevant treatment approaches for mothers and infants. Infant Ment Health J. 2006;27(4):327-43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20095.

- Barlow J, Bennett C, Midgley N, Larkin SK, Wei Y. Parent-infant psychotherapy for improving parental and infant mental health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1(1):CD010534. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010534.pub2.

- Goodman JH, Santangelo G. Group treatment for postpartum depression: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(4):277-93. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0225-3.

- Zhao L, Chen J, Lan L, Deng N, Liao Y, Yue L, et al. Effectiveness of Telehealth Interventions for Women With Postpartum Depression: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9(10):e32544. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2196/32544.

- Sockol LE. A systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating and preventing perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2015;177:7-21. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.052.

- Sockol LE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women. J Affect Disord. 2018;232:316-28. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.01.018.

- Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation. Available from: www.covidence.org.

- SBU. Bedömning av randomiserade studier. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. [accessed Aug 30 2022]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/bedomning_randomiserade_studier_tilldelas.pdf.

- SBU. Bedömning av icke-randomiserade studier av interventioner. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. [accessed Aug 30 2022]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/bedomning_icke_randomiserade_studier_tilldelas.pdf.

- SBU. Bedömning av studier med kvalitativ metodik. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2022. [accessed Oct 25 2022]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/bedomning_studier_kvalitativ_metodik.pdf.

- Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA). New Jersey, USA: Biostat Inc. Available from: https://www.meta-analysis.com/.

- Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2 ed. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

- Whiteford HA, Harris MG, McKeon G, Baxter A, Pennell C, Barendregt JJ, et al. Estimating remission from untreated major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;43(8):1569-85. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291712001717.

- Interpreting Cohen's d Effect Size: An Interactive Visualization (Version 2.6.0). Magnusson, K; 2022. [accessed Oct 25 2022]. Available from: https://rpsychologist.com/cohend/.

- Furukawa TA, Leucht S. How to Obtain NNT from Cohen's d: Comparison of Two Methods. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(4):e19070. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019070.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

- GRADE. The GRADE working group. [accessed Aug 11 2022]. Available from: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/.

- GRADE-CERQual. The GRADE-CERQual project group. [accessed Aug 11 2022]. Available from: https://www.cerqual.org/.

- SBU. Internetförmedlad psykologisk behandling – jämförelse med andra behandlingar vid psykiatriska syndrom. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2021. SBU Utvärderar 337. [accessed Aug 30 2022]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/337.

- Ammerman RT, Putnam FW, Altaye M, Stevens J, Teeters AR, Van Ginkel JB. A clinical trial of in-home CBT for depressed mothers in home visitation. Behav Ther. 2013;44(3):359-72. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.01.002.

- Honey KL, Bennett P, Morgan M. A brief psycho-educational group intervention for postnatal depression. Br J Clin Psychol. 2002;41(Pt 4):405-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1348/014466502760387515.

- Hou Y, Hu P, Zhang Y, Lu Q, Wang D, Yin L, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy in combination with systemic family therapy improves mild to moderate postpartum depression. Braz J Psychiatry. 2014;36(1):47-52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1170.

- Leung SS, Lee AM, Wong DF, Wong CM, Leung KY, Chiang VC, et al. A brief group intervention using a cognitive-behavioural approach to reduce postnatal depressive symptoms: a randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong Med J. 2016;22 Suppl 2:S4-8.

- Milgrom J, Danaher BG, Gemmill AW, Holt C, Holt CJ, Seeley JR, et al. Internet Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Women With Postnatal Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial of MumMoodBooster. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(3):e54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4993.

- Milgrom J, Danaher BG, Seeley JR, Holt CJ, Holt C, Ericksen J, et al. Internet and Face-to-face Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Postnatal Depression Compared With Treatment as Usual: Randomized Controlled Trial of MumMoodBooster. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(12):e17185. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2196/17185.

- Milgrom J, Holt CJ, Gemmill AW, Ericksen J, Leigh B, Buist A, et al. Treating postnatal depressive symptoms in primary care: a randomised controlled trial of GP management, with and without adjunctive counselling. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:95. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-95.

- O'Mahen HA, Richards DA, Woodford J, Wilkinson E, McGinley J, Taylor RS, et al. Netmums: a phase II randomized controlled trial of a guided Internet behavioural activation treatment for postpartum depression. Psychol Med. 2014;44(8):1675-89. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002092.

- O'Mahen HA, Woodford J, McGinley J, Warren FC, Richards DA, Lynch TR, et al. Internet-based behavioral activation--treatment for postnatal depression (Netmums): a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):814-22. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.03.005.

- Pinheiro RT, Botella L, de Avila Quevedo L, Pinheiro KAT, Jansen K, Osório CM, et al. Maintenance of the Effects of Cognitive Behavioral and Relational Constructivist Psychotherapies in the Treatment of Women with Postpartum Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Constr Psychol. 2014;27(1):59-68. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2013.814093.

- Prendergast J, Austin M-P. Early Childhood Nurse-Delivered Cognitive Behavioural Counselling for Post-Natal Depression. Australas Psychiatry. 2001;9(3):255-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1665.2001.00330.x.

- Pugh NE, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Dirkse D. A Randomised Controlled Trial of Therapist-Assisted, Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Women with Maternal Depression. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149186. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149186.

- Van Lieshout RJ, Layton H, Savoy CD, Haber E, Feller A, Biscaro A, et al. Public Health Nurse-delivered Group Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Postpartum Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2022;67(6):432-40. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437221074426.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II, Beck depression inventory : manual. 2 ed. San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corp; 1996.

- Dennis CL, Grigoriadis S, Zupancic J, Kiss A, Ravitz P. Telephone-based nurse-delivered interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: nationwide randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;216(4):189-96. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.275.

- Mulcahy R, Reay RE, Wilkinson RB, Owen C. A randomised control trial for the effectiveness of group Interpersonal Psychotherapy for postnatal depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13(2):125-39. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0101-6.

- O'Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Wenzel A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(11):1039-45. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1039.

- Vigod SN, Slyfield Cook G, Macdonald K, Hussain-Shamsy N, Brown HK, de Oliveira C, et al. Mother Matters: Pilot randomized wait-list controlled trial of an online therapist-facilitated discussion board and support group for postpartum depression symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(8):816-25. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23163.

- Reay RE, Owen C, Shadbolt B, Raphael B, Mulcahy R, Wilkinson RB. Trajectories of long-term outcomes for postnatally depressed mothers treated with group interpersonal psychotherapy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(3):217-28. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0280-4.

- Posmontier B, Neugebauer R, Stuart S, Chittams J, Shaughnessy R. Telephone-Administered Interpersonal Psychotherapy by Nurse-Midwives for Postpartum Depression. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61(4):456-66. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12411.

- Posmontier B, Bina R, Glasser S, Cinamon T, Styr B, Sammarco T. Incorporating Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Postpartum Depression Into Social Work Practice in Israel. Res Soc Work Pract. 2019;29(1):61-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731517707057.

- Glavin K, Smith L, Sorum R, Ellefsen B. Supportive counselling by public health nurses for women with postpartum depression. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(6):1317-27. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05263.x.

- Morrell CJ, Slade P, Warner R, Paley G, Dixon S, Walters SJ, et al. Clinical effectiveness of health visitor training in psychologically informed approaches for depression in postnatal women: pragmatic cluster randomised trial in primary care. BMJ. 2009;338:a3045. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a3045.

- Tamaki A. Effectiveness of home visits by mental health nurses for Japanese women with post-partum depression. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2008;17(6):419-27. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00568.x.

- Wickberg B, Hwang CP. Counselling of postnatal depression: a controlled study on a population based Swedish sample. J Affect Disord. 1996;39(3):209-16. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(96)00034-1.

- Goodman JH, Prager J, Goldstein R, Freeman M. Perinatal Dyadic Psychotherapy for postpartum depression: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(3):493-506. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0483-y.

- Gelfand DM, Teti DM, Seiner SA, Jameson PB. Helping mothers fight depression: Evaluation of a home-based intervention program for depressed mothers and their infants. J Clin Child Psychol. 1996;25(4):406-22. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2504_6.

- Ugarriza DN. Group therapy and its barriers for women suffering from postpartum depression. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2004;18(2):39-48. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.apnu.2004.01.002.

- Hadfield H, Glendenning S, Bee P, Wittkowski A. Psychological Therapy for Postnatal Depression in UK Primary Care Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Investigation Using Framework Analysis. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28(12):3519-32. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01535-0.

- Masood Y, Lovell K, Lunat F, Atif N, Waheed W, Rahman A, et al. Group psychological intervention for postnatal depression: a nested qualitative study with British South Asian women. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:109. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0263-5.

- O'Mahen HA, Grieve H, Jones J, McGinley J, Woodford J, Wilkinson EL. Women's experiences of factors affecting treatment engagement and adherence in internet delivered Behavioural Activation for Postnatal Depression. Internet Interv. 2015;2(1):84-90. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2014.11.003.

- Shakespeare J, Blake F, Garcia J. How do women with postnatal depression experience listening visits in primary care? A qualitative interview study. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2006;24(2):149-62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830600643866.

- Slade P, Morrell CJ, Rigby A, Ricci K, Spittlehouse J, Brugha TS. Postnatal women's experiences of management of depressive symptoms: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(580):e440-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp10X532611.

- Turner KM, Chew-Graham C, Folkes L, Sharp D. Women's experiences of health visitor delivered listening visits as a treatment for postnatal depression: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):234-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.05.022.

- Rossiter C, Fowler C, McMahon C, Kowalenko N. Supporting depressed mothers at home: their views on an innovative relationship-based intervention. Contemp Nurse. 2012;41(1):90-100. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2012.41.1.90.

- Pugh NE, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Hampton AJD, Bowen A, Williams J. Client experiences of guided internet cognitive behavior therapy for postpartum depression: a qualitative study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(2):209-19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0449-0.

- Morrell CJ, Warner R, Slade P, Dixon S, Walters S, Paley G, et al. Psychological interventions for postnatal depression: cluster randomised trial and economic evaluation. The PoNDER trial. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(30):iii-iv, xi-xiii, 1-153. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3310/hta13300.

- Stevenson MD, Scope A, Sutcliffe PA, Booth A, Slade P, Parry G, et al. Group cognitive behavioural therapy for postnatal depression: a systematic review of clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and value of information analyses. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(44):1-107, iii-iv. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3310/hta14440.

- Barnhälsovård. Barnhälsovården i Kronoberg - för en jämlik barnhälsa. Årsrapport 2021. Växjö: Region Kronoberg; 2021. [accessed Oct 25 2022]. Available from: https://www.regionkronoberg.se/contentassets/917a001acd1142f5920179050b38d09a/arsredovisning-barnhalsovard-2021.pdf.

- SFS 2017:30. Hälso- och sjukvårdslag Svensk författningssamling. Stockholm: Socialdepartementet. [accessed Oct 25 2022]. Available from: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/halso--och-sjukvardslag_sfs-2017-30#K17.

- Socialstyrelsen. Bedömning av tillgång och efterfrågan på legitimerad personal i hälso och sjukvård samt tandvård. Nationella planeringsstödet 2022. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2022. Artikelnummer 2022-2-7759. [accessed Oct 26 2022]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2021-2-7200.pdf.

- Furmark C, Neander K. Späd- och småbarnsverksamheter/team i Sverige – en kartläggning. Nationellt kompetenscentrum Anhöriga (Nka). 2018:2. [accessed Oct 25 2022]. Available from: https://anhoriga.se/globalassets/media/dokument/barn-som-anhorig/spad--och-smabarnsverksamheterteam-i-sverige--en-kartlaggning/bsa-2018-2_furmark_neander_webb.pdf.

- Cuijpers P, Franco P, Ciharova M, Miguel C, Segre L, Quero S, et al. Psychological treatment of perinatal depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021:1-13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004529.

- Hadfield H, Wittkowski A. Women's Experiences of Seeking and Receiving Psychological and Psychosocial Interventions for Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of the Qualitative Literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(6):723-36. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12669.

- Cuijpers P, Quero S, Noma H, Ciharova M, Miguel C, Karyotaki E, et al. Psychotherapies for depression: a network meta-analysis covering efficacy, acceptability and long-term outcomes of all main treatment types. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):283-93. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20860.

- Stephens S, Ford E, Paudyal P, Smith H. Effectiveness of Psychological Interventions for Postnatal Depression in Primary Care: A Meta-Analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(5):463-72. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1967.

- McPherson S, Wicks C, Tercelli I. Patient experiences of psychological therapy for depression: a qualitative metasynthesis. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):313. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02682-1.

- Lewin S, Bohren M, Rashidian A, Munthe-Kaas H, Glenton C, Colvin CJ, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings-paper 2: how to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a Summary of Qualitative Findings table. Implement Sci. 2018;13(Suppl 1):10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0689-2.

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Share via Email