Treatment for postpartum psychiatric disorders

An Evidence Map

Background

Psychiatric disorders in the postpartum period can have negative consequences not only for the affected woman, but to a great extent also for her child and the whole family. The ability to interact and care for the infant can be of great importance for the child’s health and future development.

Common psychiatric disorders include, but are not limited to, depression and anxiety syndrome. Other less common but more serious conditions are, for example, bipolar disorder and psychotic syndrome. We define an evidence gap as a method or practice for which one of the following conditions are fulfilled:

- Systematic reviews, with low or moderate risk of bias, find that there is no conclusive evidence of benefits or harms (Very low certainty of evidence according to GRADE or equivalent framework, or no primary studies identified)

- No systematic review, with low or moderate risk of bias, has reviewed the method

The lack of evidence does not mean that intervention do not have an effect. It simply means that there is a scientific uncertainty about treatment effects and that more studies or systematic reviews are needed to provide a reliable measurement.

Aim

The aim of this Evidence Map is to identify scientific evidence and evidence gaps for pre-specified areas of interest (the map), by systematically assessing and categorizing all systematic reviews on treatment of psychiatric disorders after pregnancy.

Method

A study protocol was made prior to starting the work with the evidence map.

Inclusion criteria:

PICOs

Population

Women suffering from psychiatric disorders within one year after giving a birth to a child that were alive. No limitation is made for when the psychiatric disorders started. Systematic reviews that included both a live born child and a dead child within one year after delivery are included.

Mental illness includes the following conditions

Depression, generalized anxiety disorder, acute stress response, psychosis, bipolar syndrome, eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, personality disorders, hypochondria, body dysmorphic disorder.

Intervention

Drugs (such as antidepressant, lithium and antipsychotics or neuroleptics), psychological methods (such as cognitive behaviour therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy and psychosocial support or counselling support), ECT or rTMS and other methods (such as physical activity, mindfulness, mediation, acupuncture and dietary supplement).

Control

No limitations.

Outcome

Disease symptoms, parent to infant bonding, quality of life, satisfaction with the study intervention, suicidal thoughts or attempts, suicide, thoughts of harming the baby, including thoughts of extended suicide, adverse events, quality of relationship, engagement with health services, parent-infant interaction, parental stress, parent experience of given treatment or contact with health care, sick leave, sleep, recovery rate, duration of breastfeeding or problems with breastfeeding, breastfeeding and drug interaction, parenting sense of competency, daily functioning level.

Study design

Systematic reviews.

Language: English, Swedish, Norwegian or Danish.

Search period: From 2010 to 2020. Final search September 2020.

Databases searched: Cinahl via Ebsco, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) via Wiley, Embase via Elsevier, Epistemonikos via Epistemonikos, International HTA Database via INAHTA, KSR Evidence via KSR, Medline via Ovid, PsycInfo via Ebsco. The full search strategy is available in appendix 2.

Client/patient involvement: Patient organizations have been asked for input regarding the PICO.

The PICO for this map, as well as the categories used to classify the content in the map, were outlined by the project group. In order to make sure that a relevant map was drafted, representatives from the relevant field and patient organisations/patients were given the opportunity to review the draft. After considering their comments, the draft was finalized.

A systematic literature search was thereafter designed and performed by an information specialist in order to identify published systematic reviews potentially relevant for the PICO. After the literature search was performed, two reviewers independently screened the abstracts and full text articles and selected the relevant systematic reviews. Excluded articles are listed in Appendix 1. The risk of bias in the included systematic reviews were assessed independently by two reviewers using a modified version of the AMSTAR tool. Any disagreement regarding relevance or risk of bias was solved by discussion.

Depending on the research questions addressed in the identified systematic reviews, they were classified according to the prespecified categories and are presented in the evidence map.

The report was reviewed by SBU:s internal quality assurance group, SBU´s scientific advisory board as well as external reviewers.

Results

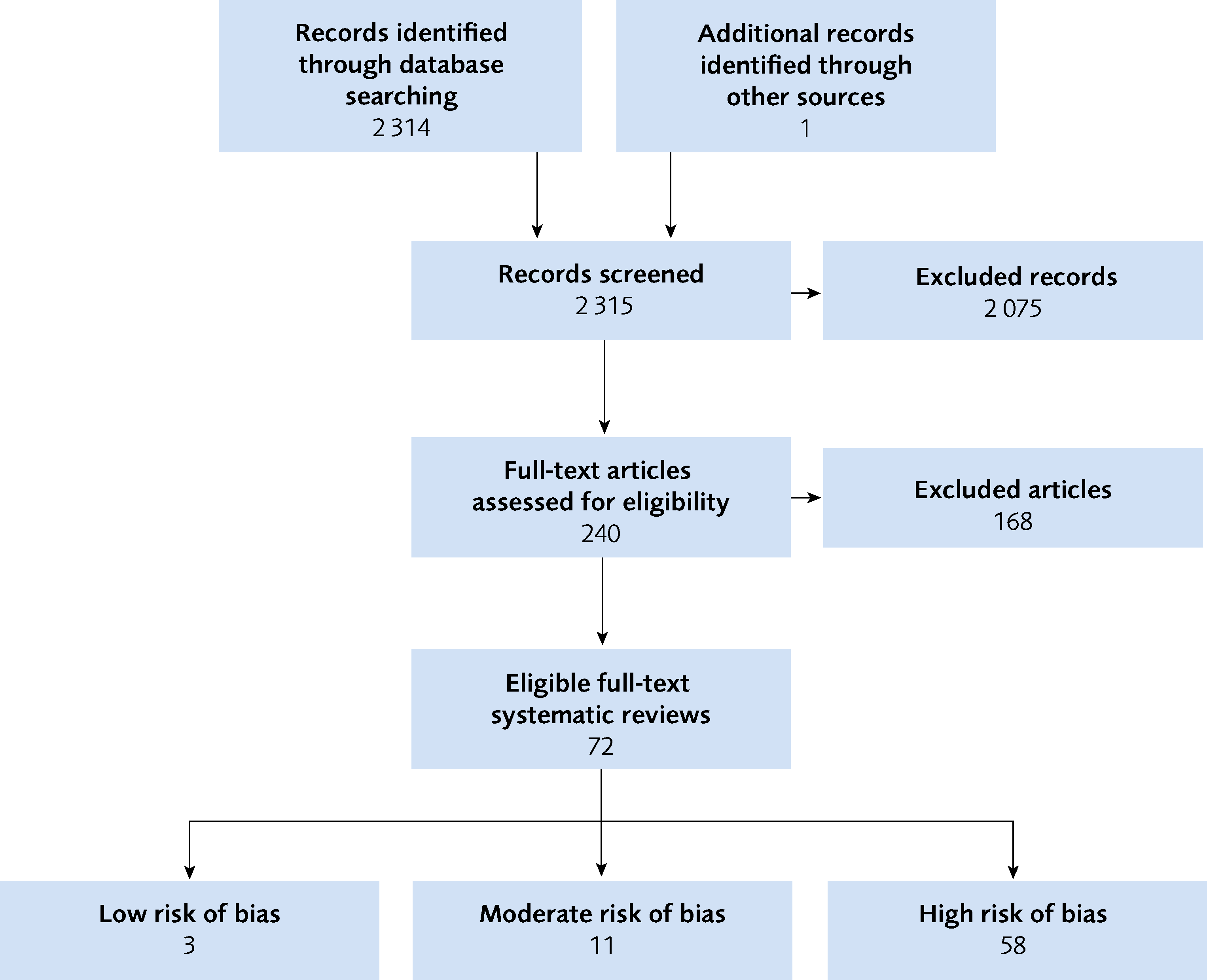

71 relevant systematic reviews were identified and provide the basis for this SBU Evidence Map (Figure 1). Out of these, 14 were judged to have a low or moderate risk of bias. All systematic reviews are presented in the Evidence map.

Conflicts of Interest

In accordance with SBU’s requirements, the experts and scientific reviewers participating in this project have submitted statements about conflicts of interest.These documents are available at SBU’s secretariat.

SBU has determined that the conditions described inthe submissions are compatible with SBU’s requirements for objectivity and impartiality.

The full report in Swedish

The full report ”Behandling för kvinnor som lider av psykisk sjukdom efter förlossning” (in Swedish)

Project group

Experts

- Adriana Ramirez, Consultant/Psychiatrist, Lecturer, Department of Neuroscience, Psychiatry, Uppsala, University Hospital

- Erik Forsell, PhD, Research and Development-Psychologist, Internet Psychiatry Clinic Centre for Psychiatry Research, SLSO & Karolinska Institutet

SBU

- Göran Bertilsson (Project Manager)

- Karin Wilbe Ramsay (Assistant Project Manager)

- Christel Hellberg (Coordinator)

- Anna Attergren Granath (Project Administrator)

- Maja Kärrman Fredriksson (Information Specialist)

- Pernilla Östlund (Program Director)

Scientific Reviewers

- Lisa Ekselius, Professor, Head physician at Department of Neuroscience, Uppsala University

- Ann Josefsson, Adjunct Professor in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Linköping University, Medical Advisor, Region Östergötland

Flow chart of included studies

Figure 1 Flow chart of included studies

References

- Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 2014;384:1800-19.

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:1071-83.

- SCB. Födda i Sverige, from https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/fodda-i-sverige/ hämtat 2020-07-20. In: Sverige i siffror. SCB, Stockholm; 2020.

- Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis CL, Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet 2014;384:1775-88.

- O'Hara MW, Wisner KL. Perinatal mental illness: definition, description and aetiology. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology 2014;28:3-12.

- Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, Whiteford HA, Harris MG. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord 2017;219:86-92.

- Jones I, Chandra PS, Dazzan P, Howard LM. Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. Lancet 2014;384:1789-99.

- SCB. Dödsorsaker efter ålder och kön år 2019. 2021.

- Esscher A, Essén B, Innala E, Papadopoulos FC, Skalkidou A, Sundström-Poromaa I, et al. Suicides during pregnancy and 1 year postpartum in Sweden, 1980-2007. Br J Psychiatry 2016;208:462-9.

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Arlington, VA; 2013.

- Zoega H, Kieler H, Nørgaard M, Furu K, Valdimarsdottir U, Brandt L, et al. Use of SSRI and SNRI Antidepressants during Pregnancy: A Population-Based Study from Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144474.

- Goodman JH, Watson GR, Stubbs B. Anxiety disorders in postpartum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2016;203:292-331.

- Bergink V, Rasgon N, Wisner KL. Postpartum Psychosis: Madness, Mania, and Melancholia in Motherhood. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:1179-88.

- Viguera AC, Whitfield T, Baldessarini RJ, Newport DJ, Stowe Z, Reminick A, et al. Risk of recurrence in women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy: prospective study of mood stabilizer discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1817-24; quiz 1923.

- Viguera AC, Nonacs R, Cohen LS, Tondo L, Murray A, Baldessarini RJ. Risk of recurrence of bipolar disorder in pregnant and nonpregnant women after discontinuing lithium maintenance. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:179-84.

- Yonkers KA, Vigod S, Ross LE. Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management of mood disorders in pregnant and postpartum women. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:961-77.

- Mandelli L, Souery D, Bartova L, Kasper S, Montgomery S, Zohar J, et al. Bipolar II disorder as a risk factor for postpartum depression. J Affect Disord 2016;204:54-8.

- SBU. Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården: en metodbok. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. [accessed April 21 2021]. Available from: http://www.sbu.se/sv/var-metod/

- Regeringskansliet. Regleringsbrev för budgetåret 2020 avseende Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering. S2019/05315/RS. In: Socialdepartementet, Stockholm; 2020.

- SBU. Vad är viktigt att mäta i forskning som undersöker behandling av depression under och efter graviditet. Framtagande av ett Core Outcome Set. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. SBU-rapport nr 314. ISBN 978-91-88437-56-3.

- LIF. Fass allmänhet, [accessed April 21 2021]. Available from https://www.fass.se/LIF/startpage..

- LV. Läkemedelsverket, [accessed April 21 2021]. Available from https://www.lakemedelsverket.se/sv.

- SBU. Granskningsmall för att översiktligt bedöma risken för snedvridning/systematiska fel hos systematiska översikter. Hämtad från www.sbu.se/metodbok den 2020-07-02 In: SBU, editor.

- Brown JV, Wilson CA, Ayre K, Robertson L, South E, Molyneaux E, et al. Antidepressant treatment for postnatal depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021.

- Scope A, Leaviss J, Kaltenthaler E, Parry G, Sutcliffe P, Bradburn M, et al. Is group cognitive behaviour therapy for postnatal depression evidence-based practice? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:321.

- Lau Y, Htun TP, Wong SN, Tam WSW, Klainin-Yobas P. Therapist-Supported Internet-Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Stress, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptoms Among Postpartum Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e138.

- Loughnan SA, Joubert AE, Grierson A, Andrews G, Newby JM. Internet-delivered psychological interventions for clinical anxiety and depression in perinatal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health 2019;22:737-50.

- Cole J, Bright K, Gagnon L, McGirr A. A systematic review of the safety and effectiveness of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of peripartum depression. J Psychiatr Res 2019;115:142-50.

- Fornaro M, Maritan E, Ferranti R, Zaninotto L, Miola A, Anastasia A, et al. Lithium Exposure During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Safety and Efficacy Outcomes. Am J Psychiatry 2020;177:76-92.

- McCurdy AP, Boule NG, Sivak A, Davenport MH. Effects of Exercise on Mild-to-Moderate Depressive Symptoms in the Postpartum Period: A Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:1087-97.

- Carter T, Bastounis A, Guo B, Jane Morrell C. The effectiveness of exercise-based interventions for preventing or treating postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health 2019;22:37-53.

- Yang W-j, Bai Y-m, Qin L, Xu X-l, Bao K-f, Xiao J-l, et al. The effectiveness of music therapy for postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 2019;37:93-101.

- Li S, Zhong W, Peng W, Jiang G. Effectiveness of acupuncture in postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupunct Med 2018;36:295-301.

- Yang L, Di YM, Shergis JL, Li Y, Zhang AL, Lu C, et al. A systematic review of acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine for postpartum depression. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2018;33:85-92.

- Li Y, Chen Z, Yu N, Yao K, Che Y, Xi Y, et al. Chinese Herbal Medicine for Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016;2016:5284234.

- Ganho-Avila A, Poleszczyk A, Mohamed MMA, Osorio A. Efficacy of rTMS in decreasing postnatal depression symptoms: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res 2019;279:315-22.

- Furuta M, Horsch A, Ng ESW, Bick D, Spain D, Sin J. Effectiveness of Trauma-Focused Psychological Therapies for Treating Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Women Following Childbirth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry 2018;9:591.

- Brown JVE, Wilson CA, Ayre K, South E, Molyneaux E, Trevillion K, et al. Antidepressant treatment for postnatal depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020.

- Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Ericksen J, Burrows G, Buist A, Reece J. Treatment of postnatal depression with cognitive behavioural therapy, sertraline and combination therapy: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015;49:236-45.

- Hadfield H, Wittkowski A. Women's Experiences of Seeking and Receiving Psychological and Psychosocial Interventions for Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of the Qualitative Literature. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017;62:723-36.

- Munk-Olsen T, Maegbaek ML, Johannsen BM, Liu X, Howard LM, di Florio A, et al. Perinatal psychiatric episodes: a population-based study on treatment incidence and prevalence. Transl Psychiatry 2016;6:e919.

- Jarrett P. Pregnant women’s experience of depression care. Journal of Mental Health Training Education and Practice 2016;11:33-47.

- Brown J, Wilson C, Ayre K, Robertson L, South E, Molyneaux E, et al. Antidepressant treatment for postnatal depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021.

- JLA. The James Lind Alliance Guidebook Version 10. March 2021. Southampton, UK: NIHR; 2021.

Evidence map

The systematic reviews in the evidence map are presented based on included population and intervention. You can filter which systematic reviews are displayed by making selections in the menu above the table. Below the table are functions for exporting the selection as an Excel file or image.

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services